- UK per-capita real income growth has been stagnating for years

- The UK has slipped down the global prosperity rankings

- These worrying trends are becoming generational in length

It is commonplace in the industrially developed world to expect that we become more prosperous one generation to the next. Yes, there are occasional setbacks, known as recessions. A century ago there was a severe, multi-decade setback characterised by world wars and economic depression.

But notwithstanding the absence of global war or economic depression, the UK has now failed to meaningfully increase domestic prosperity for many years.

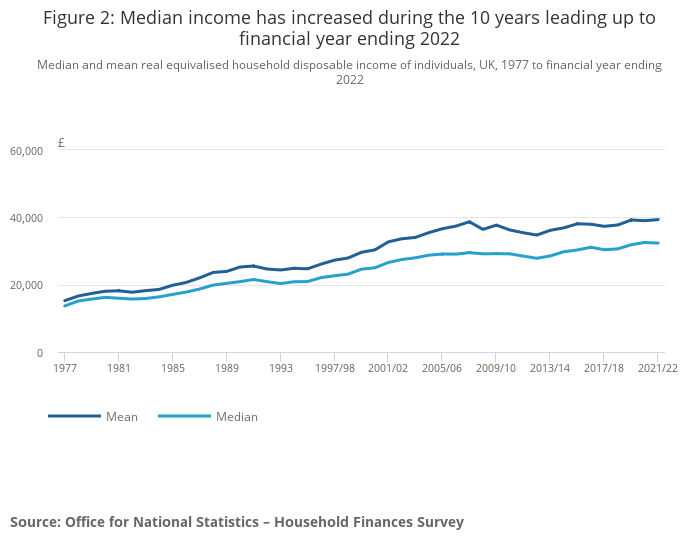

How to define prosperity? Total economic GDP may be of interest to economists, but to you and me, we’re more concerned about our household income. And to measure the latter correctly, we need to adjust that for inflation.

Moreover, excepting the wealthiest among us, we should look at median inflation-adjusted household income, rather than average, as a few wealthy households can skew the average, giving a distorted picture of the rest of us.

As a final step, we should also be concerned about disposable (i.e. after tax and other government withholdings) income, as that is what we actually get to spend how we wish. The bulk of that goes to food, clothing and shelter, but at least there is some choice involved in our specific selections of those.

With the exception of Covid-related lockdowns, the UK has managed to squeeze out at least a slow rate of real economic growth ever since it recovered from the global financial crisis of 2008-9. Yet when you strip out population growth and look at growth in per-capita terms, there has been essentially no growth at all.

Finally, when you add in the higher tax (and national insurance) burden, the net impact on real disposable median household income has been to leave us basically where we were back in 2005.

That was nearly 20 years ago. Twenty years of stagnation. And there is no world war or global depression to blame.

Also worrisome, the UK has been slipping in relative, per-capita prosperity terms versus the rest of the developed world. A recent report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is comprised of 38 of the world’s wealthiest countries, shows that the UK has slipped into the bottom half of its members for the first time.

The UK is thus underperforming as an economy both relative to its own history and the rest of the world, and these trends have been in place for many years, if not yet a full generation.

This begs the question of why? What is it about the UK that is resulting in economic stagnation and relative underperformance?

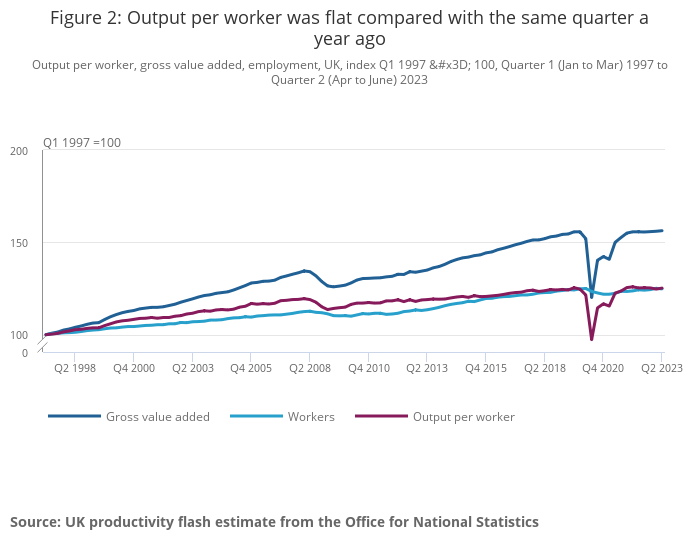

It comes down to the so-called “productivity puzzle”, that is, that the UK has been going through a prolonged period of low – indeed near zero – productivity growth.

The above chart shows output per worker, the standard measure of labour productivity. Note that, excepting the lockdown period, it has been moving essentially sideways for years following a sudden dip in 2008-9 – the global financial crisis and recession.

The workforce, however, has grown. And “gross value added”, a measure of both worker and capital productivity, has increased alongside. Hence businesses have been squeezing more value out of capital rather than individual workers. Thus the returns to capital – profits and rents – have continued to grow.

This also helps to explain the widening gap in the previous chart between mean and median disposable income growth. When capital’s share of value added grows versus that of labour, inequality tends to rise, as capital ownership – businesses and property – is more concentrated than labour “ownership”, as it were.

None of the above paints a pretty picture: the UK is a high-tax, highly regulated, over-financialised economy that increasingly concentrates income and wealth at the top, rather than one which provides prosperity for all.

If we don’t find a way to turn things around, this generation will be the first in modern UK history, outside of wartime or global depression, to have failed to hand at least a modest increase in prosperity to the next.

That’s not something of which to be proud. We can and should do better.

Until next time,

John Butler

Investment Director, Fortune & Freedom

PS While I would characterise myself as a relatively conservative, defensive, value-oriented investor, I have worked with several successful traders during my long City career. One of these is my current colleague, Eoin Treacy. Eoin employs what I would call an eclectic, agnostic investment style, searching the markets far and wide for opportunities that have compelling stories behind them but only neutral or even negative investor sentiment. Eoin then watches and waits. When that sentiment begins to turn, big moves become possible. Eoin has a knack for getting in at the right time, and for getting out quickly if an idea turns against him. Indeed, in my opinion, it is as much his risk management discipline as his idea generation that makes Eoin a successful trader. If you’d like to learn more, please sign up to attend Eoin’s four-day trader masterclass here – it starts tomorrow at 2pm.