- Economic data can be misleading

- A global recession may have already begun

- Energy is an undervalued bright spot

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies, and statistics.” – Mark Twain, attributed to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli

As the world’s largest economy, the US has a significant impact on the global business cycle – including that of the UK. That’s why I closely monitor US economic data. That said, I tend to look at it through my own lens rather than merely accept how others choose to interpret it.

During my many years working as an investment strategist for major banks, I worked closely with staff economists and learned a great deal about how to interpret US economic data. As the years went by, I combined multiple of their approaches and gradually made it my own. As I wrote earlier this year:

Although I made my name in the City of London working as an investment strategist rather than an economist, I have an academic background in economic history. This includes that of the United States, where I obtained both my undergraduate and graduate degrees.

When I started my career on Wall Street in 1993, while my knowledge of economic history was certainly useful, when it came to the day-to-day of preparing reports for clients, knowledge of the minutiae of modern economic data and forecasting played a much greater role.

Fortunately, I had good mentors, including a few who were highly critical of the way in which much economic data was reported and interpreted. They didn’t necessarily believe that the data was wrong – although they were open to that possibility – but they felt that, due to a variety of factors, there was sometimes as much or more “spin” around data, as substance.

On two occasions earlier this year, I took the opportunity to take deep data dives into US economic statistics. This included looking “behind the headlines” into the minutiae of subcategories of various aggregates. As I wrote back then, the labour market data, in particular, can be subject to much “spin” or otherwise misinterpreted:

[L]et’s look behind the headlines of the March US labour market report. As per the CNN headline above, apparently there were some 303k new jobs added to payrolls. But what type of jobs are we talking about?

Well as in the prior months, all the growth is in part-time rather than full-time work. In March, full-time job growth actually declined slightly. This continues a worrying trend. In March 2023, there were over 134 million full-time jobs. As of last month, this had slipped to under 133 million even though the working age population has been growing.

Moreover, jobs growth remains concentrated in relatively low-productivity areas such as government, leisure and hospitality. Overtime hours worked have also remained flat, something not indicative of a particularly strong labour market.

So as per above, when looking behind the headlines the March report continues to show that jobs growth, while strong on the surface, leaves much to be desired in terms of how much underlying economic strength it implies.

Lacklustre private sector full-time jobs growth stands in sharp contrast to rising public sector and part-time. But with the government chronically spending more money than it takes in, public sector growth is virtually assured. The federal budget deficit remains large in a historical comparison even though the US is not currently in a recession.

And so, I came away with the impression that the US economy was weaker than the headlines suggested. At the same time, I noticed that what I regard as the more reliable leading indicators were pointing to a slowdown ahead:

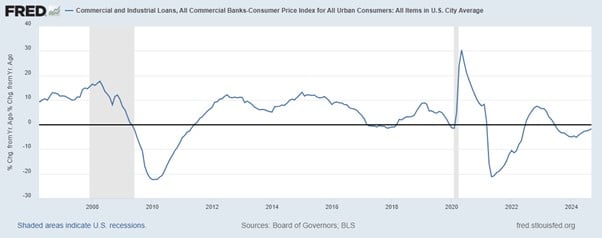

[O]ver in the private sector, borrowing is anaemic as business see few attractive investment prospects. When adjusted for inflation, commercial and industrial loan growth has been outright negative for months, something that normally only takes place when the economy has entered recession.

Around that time, industrial commodity prices were also declining, a possible confirmation of a general global economic slowdown.

Bringing that all together, my conclusion was that the US-led global economy was already weak and likely to slip into recession either this year or early next.

During the late summer, the consensus view began to move in this direction. As I wrote back in August:

When even the most left-leaning, “Bidenomics”-cheerleading US economists begin to talk about a possible recession ahead, you should conclude we might well already be in one.

One of the most prominent such voices is Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, who writes a column for the New York Times. This past week’s contribution was titled “The Economy Is Looking Pre-Recessionary”.

What? As recently as June he was writing articles with subtitles including “The Economy is in Good Shape”, “How America Avoided Recession” and “The Soft Landing is Almost Here”.

Why the sudden change of tune?

Because it has become so obvious now that a US recession is on the cards that even Baghdad Bob would have to acknowledge it.

I’ve written on multiple occasions prior about things such as bank lending, factory orders, inventories and the hidden weakness in labour market reports. I’m not going to rehash all of that here. I don’t need to. Everyone else, even Democratic cheerleaders such as Krugman, are now doing it for me.

But is that reappraisal now being reappraised? Last week, the US labour market headline data was strong yet again. Is the economy perhaps re-accelerating rather than decelerating?

Let’s look behind the headlines yet again, shall we?

According to the September jobs report, the US added 254k jobs last month. That’s a large although not blowout figure. The unemployment rate remained unchanged at 4.1%.

But what type of jobs were added? Well, of the 254k, 223k were in the private sector rather than public. That looks good, as private sector jobs tend to be higher productivity jobs than public sector jobs, which must also be taxpayer-funded.

But essentially all of that 223k private sector jobs growth was in healthcare, hospitality and leisure, amongst the lowest-productivity private sectors of the economy. Yes, these jobs are important, but they don’t drive economic growth forward the way manufacturing, transportation and technology do.

Indeed, when it comes to high productivity but also highly cyclical manufacturing jobs, these have now outright declined for two months running. That’s a warning sign that a recession might have already begun.

That said, one should not read too much into the monthly data, as they can be volatile and subject to large revisions. So, what do the year-on-year comparisons look like?

One thing that stands out is the rise in part-time work, which has increased by roughly 1 million, more than accounting for total jobs growth. This implies that full-time jobs have actually declined slightly over the past year. Take public sector jobs out of the equation and the decline has been even larger.

So, we have an economy adding low-productivity, part-time jobs and shedding high-productivity, full-time jobs. Does that sound like a strong economy to you? Of course not. It looks like one slipping into recession.

Things are also likely to get worse rather than better. Businesses aren’t borrowing, implying that they aren’t investing in the future. Businesses that don’t invest tend not to hire more workers, especially full-time ones.

As is plain to see, when adjusted by inflation using the US CPI index, commercial and industrial (C+I) loan growth has been outright negative for over a year now:

As goes investment so goes long-term profit growth. It is hard to imagine healthy, long-term profitability without a healthy amount of investment. Hence investors should be concerned that investment is so weak.

It might even be weaker than official economic statistics indicate. To give an accurate picture of an economy, data need to be adjusted for inflation. If inflation is being underestimated, then investment and growth will appear stronger than they really are.

In part 2, we’re going to explore the possibility that official inflation data is indeed understating the true rise in the cost of living. If that is so, then the US, UK and most of the global economy may have already been in recession for over a year now.

Regardless, there is one relatively bright spot for investment at present: energy. Here at Southbank Investment Research, we’ve been researching and writing regularly about the surge in energy, power generation and essential electrical infrastructure investment for over two years now.

Over at Southbank Growth Advantage, editors James Allen and Sam Volkering are currently recommending multiple ways for investors to take advantage of several current energy investment trends – including nuclear. If you’d like to learn more, you can do so here.

Until next time,

John Butler

Investment Director, Fortune & Freedom