I’m over lithium.

There. I said it.

I understand the hype surrounding the metal. Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries were a game changing scientific breakthrough in the 1970s, when lead acid batteries were common.

And all of this excitement about lithium sparked a modern gold rush to find ever increasing amounts of this “white gold” when its electric vehicle (EV) applications were revealed.

As an Australian, I should be championing it.

A local mining magazine recently wrote that exploration spending by Australian-listed miners hit an eight year high at the end of last year, largely driven by the hunt for new lithium. Some AU$2 billion is going to spend trying to find more lithium locally.

Currently 66% of the world’s lithium comes the salt flats of Chile, Argentina, China and Tibet. Often called “salars”, mining from lithium brine is a much cheaper way to extraction lithium. Yet it’s extremely water intensive, damages local agriculture and risks potential water contamination.

In contrast, Australia has the hard rock type of lithium deposits called a pegmatite – which is essentially a large rock with clumps of smaller and differing mineralised crystalised and rocks inside.

What makes these lithium pegmatites so special is a mineral called spodumene, a purer form of lithium that the market prefers. Plus … these pegmatites often host other and elements like tantalum, niobium and tin.

Pegmatites are more costly to extract than brine, but spodumene can be produced into both lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide in one step. This is unlike lithium from the salars which takes a couple more steps to get a lithium hydroxide.

Shoving the geology lesson aside for the moment, it’s odd that I would say I’m “over” a mineral when the market is screaming for more. Especially when everyone in Australia is trying to get in on the action.

Can you blame them? The lithium carbonate price has quadrupled in the past 12 months.

Elon Musk, EV tycoon and dealmaker extraordinaire, is threatening to buy his own lithium mine to secure supply of the stuff. Exploration budgets for lithium globally are rapidly increasing.

So clearly, everyone “gets” it except me…

But that’s the problem with lithium. It’s so hot that it’s ripe for disruption.

Running against the hype cycle

“Did you see our lithium intercepts,” a managing director of a highly speculative Australian explorer said to me when I was in Sydney at a resource conference at the start of the month.

“I did, but… meh, I’m not really digging the lithium story any more.” As the words fell out of my mouth, so did his face. And that was the exact moment I realised I should have chosen my words more carefully.

However, this firm knows they are one of my favourite exploration stocks going around. The friendship isn’t ruined. Alas, I cannot name them. They’re too small. Their too hard to access for folks in the UK. Plus, any name dropping or even hinting at who they are risks me running afoul of financial advice laws in two different countries.

But… let’s get back to my point.

This sometime exploration junior has decided that it is joining the rest of the pack and looking for lithium.

This happens from time to time. When one commodity runs hot for a while, some juniors will almost invariably decide to get in on the action and shift their focus accordingly.

It’s frustrating as analyst when companies do this (stick to what you’re good at I may have yelled at a screen once or twice). But sometimes – if you want to attract private equity (PE) investors or shareholders – you need to prove to them you’re not a one-trick pony. (Actually, you don’t need to prove it: you just have to stop potential investors from thinking of you as a one-trick pony – which is not quite the same thing.)

This means that you look for other projects that complement the current ones.

So why am I not loving lithium right now? Everyone else does. By all reports, the demand trend is only going up. As governments tweak and toggle with emission restrictions people are being driven to hybrid and electric vehicles at great speed. No doubt crippling petrol prices will only nudge people further along the past faster.

A persistently unreliable source of unsought opinion told me that I needed to ditch my gas-guzzling four wheel and get a sensible electric car in the next year or two.

But that’s the problem.

When everyone is looking in the same direction, it risks no one checking the blind spot…

There’s probably a better option than lithium

Seizing the moment to indulge my love of rocks, it’s here we reach the crux of my problem for lithium: It’s not that good.

Look, don’t get me wrong, from a chemistry point of view it’s the best we have. From an energy density per kilo of mass point of view, wood creates more energy per gram than these batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries only have so many recharge cycles, they are costly to make and extremely expensive to recycle. In fact, it costs more to recycle them, then to dig all the stuff up again and make it into a new battery.

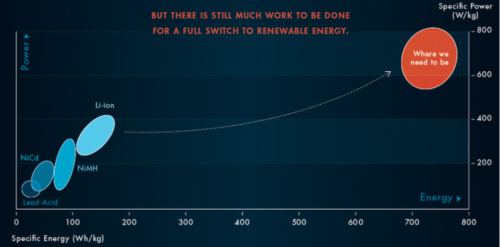

To boot, the current chemistry has reached the power limit. Ships, trains and airplanes can’t be run on lithium-ion batteries. All three forms of transport that underpin our supply chains.

For a full switch to renewable energy sources, much more research needs to be done to create higher.

Lithium-ion battery was a catalyst, but higher power sources are needed

Without question, lithium-ion batteries were a catalyst to the energy transition, but they won’t help us complete it.

The quadrupling in lithium carbonate prices in the last year will only encourage research to look at cheaper options in the coming years. Already there is work underway on replacing lithium with sodium.

The limits of lithium have been known for some time, but increasing demand plus extreme price rises create an extra incentive to speed up the next technical innovation.

The question is, if I’m not excited about lithium, what does excite me now?

Well, there’s a handful of things in the answer, and they are about as old as mankind.

Watch this space…

Until next time,

Shae Russell

Contributor, Fortune & Freedom