- Populism is on the rise globally

- Some claim this threatens democracy

- But does history really bear that out?

Former Prime Minister Churchill once famously quipped that democracy was the worst form of government, save for all the others. He had a point.

Democracy is messy when viewed close up. Those with some preconception of how an orderly society should function see disorder and chaos even when whatever bubbles up from below doesn’t quite fit with their preferences. They tend to call this aspect of democracy “populism”.

There is a natural tension between whatever elite exists within a society and everyone else. The ancient Greeks, among others, understood this, as evident in their myths and literature.

The terms “aristocracy”— rule by the elite — and “democracy” — rule by all adult citizens (however defined) — are both Greek and describe quite different ways of governing a society. What’s interesting is that the Greeks could never really decide which was better. Plato and Aristotle, among others, disagreed deeply about this.

I was reminded of this ancient debate at an event in London last month. It was a multi-faceted and quite relaxed symposium of sorts that sought to explore some of the more intractable social issues of our time.

One of those discussed was populism. A political pundit who writes for a prominent British magazine opined that, “If left to run unchecked, the current wave of populism sweeping through the west risked undermining democracy.”

While he made his point at length, he did so within a fairly narrow window. That is, he only mentioned a handful of issues where, in his opinion, populist views are not only radical but downright dangerous. These included energy, climate and immigration policy.

And so, keen amateur debater that I am, I put myself forward to ask a question: What about imperialism and war? History demonstrates that these tend to undermine democracies, including both Athens and Rome. So, if all major parties in a democracy are generally pro-imperialism and war, does a populist anti-imperialism or anti-war movement still undermine democracy?

Silence briefly followed. Then he offered something along the lines of, “That may be the case historically, but in the modern world, in which democracies do not go to war except against tyrants, populist anti-war movements are indeed dangerous.”

I suppose it all depends on whether you believe that democracies should function as policemen outside their own borders. That’s become quite a popular view post-9/11, with the US having become involved in regime change in multiple countries.

Regardless, alongside the perceived rise of economic inequality post-2008, anti-war isolationism has been on the rise in recent years. And notably, unlike foreign interventions that haven’t necessarily met with much success, populism appears to be on a winning streak.

Last month, in two different hemispheres, populists scored major political victories. Javier Milei, a self-described “anarcho-capitalist” won in a landslide election as Argentina’s new president on a platform that included, among other things, abolishing the central bank and axing multiple government departments.

In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’ populist Party for Freedom won the most seats in the Dutch Parliament, making it difficult, if not impossible, for the other, non-populist parties to form a government.

That populism is taking hold in the Netherlands and it’s telling. We English may claim to have the “mother of all parliaments” but historians generally agree that the modern concept of a “middle-class democracy” not dominated by a landed aristocracy originated in the Netherlands, not the UK.

For those unfamiliar with Dutch history, these are the folks who revolted against the most powerful empire of the time: Habsburg Spain. The Dutch fought a long and bloody war to gain their independence, which they subsequently won.

As they grew increasingly wealthy, they found themselves drawn into conflict with both France and England. As a much smaller country, they perceived themselves as the underdog in both cases. Indeed, at times, the English and French ganged up on the Dutch simultaneously.

Dutch democracy thus has deep nationalist and populist roots. It could be argued that, were it not for this national character, the Netherlands would have failed to defend and maintain its national independence through the centuries.

Meanwhile, across the pond, recent polls indicate that populist presidential candidate Donald Trump is now leading in key swing states. Although the election is still a year away, this is yet another possible success-in-the-making for what increasingly appears to be a global populist movement.

I wonder what Churchill would make of all this. The British Empire is long gone, replaced in some aspects and extent by an American one. Democracy has spread across much of the world, although this has not led to peace and economic growth everywhere it has been tried.

When a democracy doesn’t deliver on its promises, populism is perhaps the inevitable result. But is that a danger to democracy or an entirely healthy way for a democracy to re-orient itself to focus on the issues that matter most to the citizens?

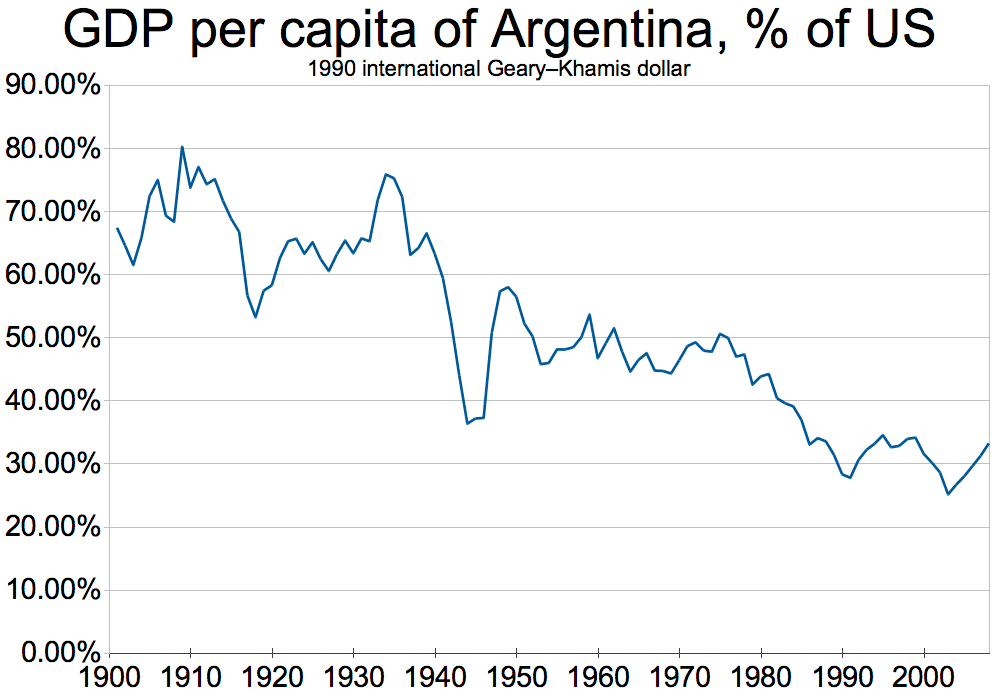

In Argentina, economic underperformance has been chronic for over half a century. A country rich in natural resources that, on paper, should be as wealthy as almost any other large, modern democracy is failing its citizens.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

Are those living in Europe or North America really going to wait until things get that bad before their own populist movements force a major re-orientation of government policy? If the highly prosperous, historically progressive Dutch are any indication, apparently not.

Until next time,

John Butler

Investment Director, Fortune & Freedom