Inside this issue:

- The US economy appears strong on the surface

- Beneath, it appears weak

- The private sector may already be in recession

Back in early February I wrote about how economic data is reported in ways that spin, obscure or mislead about what is really happening. This seems particularly true of late when it comes to US labour market data.

This is important. The US economy is arguably the single most important driving force for global financial markets, including the UK stock market. Our investment service, Southbank Wealth Advantage, recently implemented a “Recession” portfolio specification in part due to growing signs that the US economy is slowing down and will probably tip into recession either later this year or next.

The headlines appear to tell a different story, one that has been supportive of global stock markets in recent months. For example, last week it was reported that the US economy added 303k new jobs.

That’s a big number, larger than what economists generally expected. A CNN headline read: “March jobs report comes in hot: The US economy added 303,000 positions last month”.

So, does this contradict the recession view mentioned above? No. Indeed, a look behind the headlines suggests the opposite.

Let’s quickly recap my prior look behind the US labour market headlines from December into early February:

[T]he report divides employment status up into full-time and part-time. And guess what? Over the past year, including the January report, there has actually been a small decline in full-time jobs. All the growth has been in part-time jobs instead.

[T]he composition of jobs has been changing. As former US Federal Budget Director David Stockman explained when describing the December jobs data:

Fully 183,000 or 85% of the 216,000 new jobs reported for December 2023 were in the low-pay, low-productivity sectors of government, leisure & hospitality, retail trade and health and education services. Indeed, owing to the short weekly hours in many of these sectors, the index of aggregate hours worked actually declined during December from the November level.

That’s right. The actual deployment of labor hours in the nonfarm economy shrank during December, notwithstanding the ballyhooed 216,000 gain in the nonfarm headcount.

Borrowing his approach, in January, the low-productivity sectors he lists above comprised over 300k of the total 353k payrolls increase. And as per above, aggregate hours worked declined yet again.

Pulling it all together, “Bidenomics” might be creating jobs. But it is losing high-productivity full-time jobs and gaining primarily relatively low-productivity part-time jobs, public sector jobs and leisure and hospitality jobs.

Does that sound like a strong economy to you?

It doesn’t to me…

Now, let’s look behind the headlines of the March US labour market report. As per the CNN headline above, apparently there were some 303k new jobs added to payrolls. But what type of jobs are we talking about?

Well as in the prior months, all the growth is in part-time rather than full-time work. In March, full-time job growth actually declined slightly. This continues a worrying trend. In March 2023, there were over 134 million full-time jobs. As of last month, this had slipped to under 133 million even though the working age population has been growing.

Moreover, jobs growth remains concentrated in relatively low-productivity areas such as government, leisure and hospitality. Overtime hours worked have also remained flat, something not indicative of a particularly strong labour market.

So as per above, when looking behind the headlines the March report continues to show that jobs growth, while strong on the surface, leaves much to be desired in terms of how much underlying economic strength it implies.

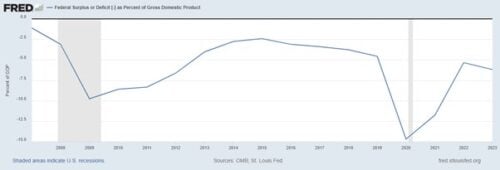

Lacklustre private sector full-time jobs growth stands in sharp contrast to rising public sector and part-time. But with the government chronically spending more money than it takes in, public sector growth is virtually assured. The federal budget deficit remains large in a historical comparison even though the US is not currently in a recession.

The US economy is thus living on borrowed money and time as the relatively less-productive public sector siphons jobs away from the private.

By contrast, over in the private sector, borrowing is anaemic as business see few attractive investment prospects. When adjusted for inflation, commercial and industrial loan growth has been outright negative for months, something that normally only takes place when the economy has entered recession.

That time is coming. A general downturn is inevitable. If history and leading indicators are a guide, it could begin already later this year. Stock markets tend to smell economic trouble at least a few months in advance, sometimes a few quarters. Hence I’m already taking precautions with my portfolio, as well as implementing them into my strategy for my subscribers over at Southbank Wealth Advantage.

With this forward thinking, such a strategy – being diversified, risk-weighted and fully invested – is thus appropriate for longer-term, retirement-oriented portfolios. Hence some readers might be interested to learn that we are currently offering an initial subscription at a discounted price, for a limited time only. If you’d like to learn more about what Southbank Wealth Advantage might be able to do for your pension pot, please click here.

[Capital at risk.]

Until next time,

John Butler

Investment Director, Southbank Insider