[This issue was originally published on 30 January 2023]

In this issue:

- Nigel Farage: politicians will follow the public on nuclear power (at last)

- Nick Hubble on the nature and extent of the nuclear comeback

- Eoin Treacy finds an unusual way to profit from the revival of nuclear power

|

It was a disastrous scene of almost biblical proportions. A huge tsunami had engulfed the Fukushima power plant in Japan and three nuclear reactors were in danger of meltdown. Was another Chernobyl upon us?

The doomsayers across the western world were vociferous: nuclear power must come to an abrupt halt. It seemed at this moment that everything that had been developed since the end of World War II was at an end. We were turning our backs on an effectively inexhaustible carbon dioxide-free energy.

The response in countries like Germany was immediate. Nuclear energy would play no part in their future. At least, that was the plan at the time…

In the intervening years, the taxpayer subsidised renewable energy sector boomed, with gas providing the backstop.

But just a decade on from that frightening moment in Fukushima, there is a growing realisation that energy supply security is vital if the modern world is to function.

The Ukraine war, a huge spike in natural gas prices, and dire warnings about blackouts have made us realise that just-in-time international supply chains have their limitations. National security is back as a top political consideration. All of this at a time when climate change is a huge political consideration for much of the media.

Different sections of society are reaching the same conclusion about the obvious solution to all of these challenges. And a rapid shift in public opinion on nuclear energy has occurred. Although behind the public, our western politicians are showing a marked change of tone too.

Nuclear energy provides baseload power, which means a constant, reliable supply of electricity. The advocates for renewables will sing from the rooftops on days that wind makes a big contribution to the grid, but will go very quiet in calm conditions. As I write this, the UK is readying emergency coal fire power stations once again to cover for the wrong sort of weather.

The biggest problem here in the UK would be a large anticyclone sitting over northern Europe in midwinter. Without sufficient fossil fuel backup, the lights would literally go out.

Given all this, the logic that a far bigger share of our energy mix should come from nuclear will, in my view, become irresistible. It is already happening. Even the German Greens have shifted their position in favour of nuclear, if only in the short term, for now.

The public are making their minds up in a very significant way. Many now realise the sheer stupidity of the Fukushima plant being built on a tsunami prone fault line without sufficient safety measures.

In northern Europe, regular opinion polling shows that in countries such as Sweden, support for nuclear power is now running at astonishing levels, with 78% of the population strongly or somewhat supporting the industry. Just 11% are now strongly against.

A similar pattern can be found in Belgium, where 72 percent of people see the industry as part of the solution to climate change. In Germany and elsewhere there are genuine U-turns happening, though support for continuing the life of existing plants does still exceed support for building new ones.

Perhaps the key to the future of the industry and the price of uranium will be the political decisions that are taken in the United States. 2016 polls showed 54% opposition to domestic nuclear energy use. Recently support rocketed to 72%.

Politicians are far better at following than leading, so I will let you draw your own conclusions about what happens next.

There is huge debate and much excitement about the future use of small modular reactors (SMRs). They are the future. The UK’s submarine fleet already has miniature versions of them, working with incredible efficiency. We will no longer need to build the 1960s monstrosities as the plants become very much smaller. I envisage that the French will build these on the existing sites of their ageing stock of reactors.

There is still much design work to be finalised for full proof of concept. Nevertheless, the day is coming when the years needed to become operational will be far shorter too.

As with supersonic flight, we will look back in a few years and ask ourselves how we turned our backs on modern innovation. I firmly believe there will be a great deal more nuclear energy by the mid-2030s.

Nigel Farage

Editor, The Fleet Street Letter

The Nuclear Renaissance began last year

Men and nations behave wisely when they have exhausted all other resources.

– Israeli politician and diplomat Abba Eban

|

The meaning of Renaissance is “re-birth” or “revival of interest” in something. This implies it was previously held, but lost. And that is precisely what happened to nuclear power over the past 12 years. We had it, lost it and found it again.Twelve years ago, the world turned its back on the only known proven, reliable, cost-effective, geopolitically secure, strategically beneficial and green source of energy.

The result was precisely what you would expect: an energy crisis, huge environmental damage, a geopolitical crisis, lower living standards for many, a discredited environmental movement, unreliable power, industrial shutdowns, a winter of discontent, a struggling energy grid, inflationary pressures and much more.

Why did we make this obvious and predictable mistake? That’s the worst part. It was for no good reason whatsoever. The Fukushima disaster proved, once again, that nuclear power is remarkably safe compared to its peers, even when it goes badly wrong.

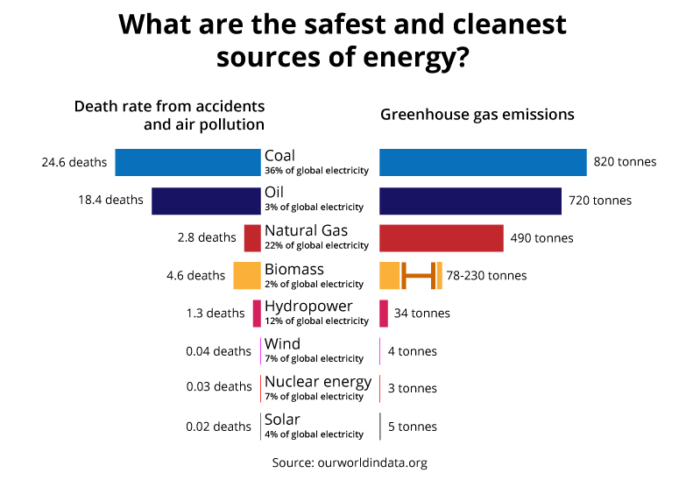

Research summarised by Our World In Data concludes that nuclear power is the second safest and second lowest polluting form of energy, pipped only by solar. Remove the deaths from a badly mismanaged Chernobyl plant and it may even be the safest.

Comparisons to Europe’s favoured biomass, nuclear is 153 time safer and about 30 times cleaner.

In the midst of 2022’s energy crisis, people began to wonder…

Where would the world be today if we had continued to pursue nuclear power?

Would our emissions be as high? Would pollution related health issues be as common?

Would Russia have invaded Ukraine without the leverage of Europe’s reliance on continuous flows of Russian gas to provide baseload power?

Would Germany be burning coal for electricity and wood for heating while shutting down its industries?

Would energy grids be struggling under the strain of fluctuating power supply from renewables? Would there have been blackouts in Texas?

Would Dutch greenhouses be shut down and would there be a fertiliser shortage?

Would inflation have surges as high? Would our energy bills risk bankrupting us and our businesses?

Would economies need energy bailouts so large they risk a sovereign bond crisis?

The answer is that nuclear power promised the precise solutions we lacked in 2022. And there’s nothing like hindsight to make people wake up.

Polling has moved back in favour of nuclear power

The Fukushima disaster tipped public opinion around the world against nuclear power. Governments announced plans to abandon the politically risky energy source at various differing speeds. And, in my judgement, the subsequent renewable energy boom began as a result of this. But that’s another story.

In 2022, opinion reversed back in favour of nuclear all over the world.

In Australia, a most nuclear power sceptic nation according to my own experience, majority support has changed sides in rapid fashion, reaching a high of 70% in support by some measures.

In 2016, support for nuclear power dipped below the majority in the United States. In 2021, that reverted to a majority favouring nuclear.

In Germany, opposition to new nuclear plants remains, but opinion radically shifted from 40% to 68% in favour of keeping existing plants running longer than was government policy in 2022.

In the UK, the share of those strongly supporting nuclear power is rising, those strongly against are falling, and those in support far outweigh those against.

In March 2022, Japan Times reported, “Majority in Japan backs nuclear power for first time since Fukushima,” and, “That’s up from 44 percent support for the restarts in a similar survey in September.” The support hit 60% in August according to a former International Energy Agency executive director.

In Sweden, support for new reactors surged from below 30% in 2018 to a high just under 60% in 2022, while support for phasing out nuclear power declined rapidly.

In South Korea, a president who was elected in 2017 on the promise to change government policy and abandon nuclear power was replaced by a president who promised to change government policy and expand nuclear power.

The underlying change is clear. All around the world, people are back in favour of nuclear energy, especially thanks to 2022’s crises.

But that is not necessarily enough to convince the decision makers of our energy systems – the politicians.

Nuclear is unavoidable in a world focused on emissions and energy security

Energy, a bit like investing, is a game of alternatives. Even if you don’t like any of the options, you still have to choose the least bad option that actually works.

Europe’s attempt to deny this in 2022 resulted in economic shutdowns, energy rationing, blackouts and more. But, in the end, the energy system is there to feed the economy’s demand, and the economy is not there to tide over the energy system’s shortcomings. At some point, serious energy supply must be brought online.

The electrification of many of our fossil fuel using industries and behaviours also means that electricity demand is going to boom. The International Energy Agency estimates that nuclear generation needs to double by 2050 to hit net zero targets. Transitioning the economy to electricity to minimise emissions, while starving it of electricity over emissions concerns, is not going to work.

Given the underlying challenges of our long list of potential sources of power which we can choose from, we can safely say that nuclear will have to be part of our energy mix in the future. It is the second safest, second cleanest form. It takes up a tiny fraction of the space needed by other potential energy sources. Nuclear also has the highest capacity factor – the amount of energy actually created relative to how much it is capable of creating. Other forms of energy have significant downtime, in other words.

Nuclear fuel is found in geopolitically safer jurisdictions like Australia. Moreover, it can be stored and stockpiled economically to prevent shortfalls, and it does not pollute the environment like oil.

Energy analysts and consultants Doomberg, not usually ones to make a point in dramatic fashion, put it like this:

There is simply no path to a low carbon economy without a massive nuclear power renaissance. If you are simultaneously opposed to fossil fuels and nuclear power, you are for mass starvation and extreme human suffering (whether you realize it or not).

So, the people and the economic reality of nuclear power have shifted in its favour. Now, even governments around the world are finally waking up to the need for nuclear power. This has triggered a radical shift in the demand curve for nuclear technology, hardware, fuel and infrastructure.

Let’s quickly take a tour of the world’s key policy shifts to get an idea of just how rapidly politicians around the world have executed their backflips on nuclear power…

UK

In April 2022, the UK government outlined its plans for nuclear power. These include building eight new reactors plus smaller modular reactors, set to provide 25% of the UK’s electricity demand by 2050.

Nuclear currently provides about 15% of the UK’s power, but half of that is set to be shut down by 2025 and much of the rest by 2030. Thus, a pipeline of new projects will be required: the government has founded an organisation called Great British Nuclear to provide this pipeline.

An October 2021 Independent Review of Net Zero report commissioned by the government concluded that nuclear power is “a no-regrets option” for the UK.

Japan

Japan’s government totally reversed its policy to phase out nuclear power in December 2022. It went from rejecting new plants, ceasing production from existing plants and closing aged plants with the aim of ending nuclear power by 2030, to opening new plants, prolonging the lives of existing plants and restarting those that were shut down.

The boom has already begun, with utility companies applying for 27 reactor restarts, 17 passing safety checks and 10 resuming operations.

Despite the recent boom, nuclear energy accounts for less than 7% of Japan’s energy supply. Achieving the government’s goal of raising its share to 20-22% by 2030 will require about 27 reactors, from the current 10. Their share of power generation would still be below the 30% before the Fukushima disaster.

Most nuclear reactors in Japan are more than 30 years old. While these will be able to get their lives extended by ten years, this implies a significant construction boom for the renewal and replacement of nuclear power in Japan in the coming decade.

South Korea

In the March 2022 presidential elections, a pro-nuclear candidate defeated an anti-nuclear incumbent who planned to phase out nuclear power.

The country’s 26 reactors produce about a quarter of its electricity, but the new president wants to increase this to at least a third. Plans include extending the life of existing reactors and building new ones.

United States

The US has the world’s biggest nuclear power industry with 93 reactors providing 20% of electricity. But the decline is precipitous with 13 reactors closed since 2013 and half at risk of closure by 2030.

That decline may have been arrested in 2022 with the government reversing policy on the closure of Diablo Canyon. But only two nuclear plants are under construction.

In 2020, Congress created a national uranium reserve to guarantee annual purchases from US companies which had been begging for support to keep their mines open. This implies a longer term strategy for nuclear power.

France

France is the world’s second largest nuclear power producer, but places by far the highest proportion of its electricity production on nuclear at 70%. The 56 reactors also provide Europe with 15% of its total power via exports.

President Emmanuel Macron committed to building six new reactors at a cost of nearly €52 billion. And government-owned power utility EDF is set for nationalisation to make the government’s plans happen.

France is also a leader in nuclear technology alongside the United States, making the global nuclear boom an opportunity.

China

China has grown its nuclear power capacity twenty-five-fold since 2000 and doubled it since 2015. In 2019, Chinese nuclear power represented about a quarter of global capacity. But France and the United States continue to have greater nuclear power capacity for now.

It is estimated that China’s nuclear generating capacity must increase the share of nuclear power in the country’s energy mix from 4% to 28% by 2050 if the country is to play its part in limiting the global temperature rise to below 1.5 °C.

To achieve its emissions commitments, China’s government plans to build more than 150 nuclear reactors by 2035 – more than the rest of the world in the last 35 years. It currently has 49 operational power plants and 17 under construction.

China’s government aims to be self-sufficient right across the nuclear power sector, from technology to fuel supply. And then it hopes to export nuclear technology.

Estimates from Reuters are that China has secured enough uranium supply for ten years of operations. It is engaging heavily with the world’s largest mining country (by output), Kazakhstan.

The facts haven’t changed, but politicians and the public have changed their minds

What’s notable about these policy shifts, with the exception of China and France, which never transitioned away from nuclear power, is the clear 180-degree reversals from previous policy positions. There was no time spent on an awkward in-between. Nations went from ending nuclear power over Fukushima to expanding it over Ukraine.

Investors noticed the change, with the Nuclear Energy Institute estimating that more than US$5 billion was invested into advanced nuclear companies globally over the past 12 months.

Although the increases in the anticipated amount of nuclear energy being produced is often small as a percent of total energy produced, the actual amount of the increase is large because total electricity demand is growing.

The retirement of old plants also implies that new ones will have to be built to replace them. This suggests that nuclear power plant technology and hardware companies will also benefit more than the overall numbers suggest.

All that, in turn, means that demand for nuclear technology, nuclear fuel and reactors is extremely likely to surge in coming years, starting yesterday.

But what of supply?

EDF and Westinghouse Electric need rescuing

Two of the world’s key nuclear technology and hardware providers have had a rough few years.

France’s EDF is in the process of being nationalised after struggling with its debt loads. The US’ Westinghouse Electric, responsible for the technology in about half the world’s nuclear reactors, went bankrupt in 2018, was acquired by private equity investors and recently sold on again for a sixfold gain. The buyers were a consortium of the seller’s own subsidiary and XXXXXXXXXXX, a major uranium miner.

As EDF and Westinghouse are out of reach, there is a distinct lack of investment options when it comes to nuclear technology. This creates an immense opportunity for the remaining nuclear tech companies in the world, as Eoin Treacy discusses below.

What of nuclear power’s key fuel – uranium?

Structural undersupply

As with all commodities, uranium is subject to the boom-and-bust cycle driven by the delay in getting production online. During a glut, the price plunges, discouraging investment. This creates the subsequent shortage, which triggers the price to surge. That surge incentivises production, which eventually leads to a glut.

The question for investing in commodities, then, is always a question of where in the cycle one finds oneself.

As you can imagine, the poor demand prospects for nuclear in the wake of the Fukushima disaster left the price of uranium tumbling, as a glut began. A long list of production projects has even been mothballed, with uranium mining in the United States recently approaching nothing.

Russia, which mines 6% of the world’s uranium, has added supply risks. Its neighbour Kazakhstan, the world’s leading uranium producer, is also politically risky, and so many Western utilities are seeking to avoid buying there.

Recently, though conditions in the uranium glut began to change.

XXXXXXXXXXX, the price of which is up almost twenty-fold since the pandemic lows, is preparing to restart the Langer Heinrich mine in Namibia by the first quarter of 2024 after closing it in 2018.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXX is also reviving its McArthur River mine and Key Lake operations.

But these are mostly still paused legacy mines that are reopening. Exploration for uranium has crashed since its heyday in 2008. The total budget for such exploration today is about a fifth of its peak.

Supply and demand determine price

What do you get when you combine dilapidated and reluctant supply and resurgent demand? Technically, and in pretty short order, you get a deficit. Canada’s Scotiabank estimates that there will be a steady deficit going out to 2030 after years of oversupply. But deficits really just mean price spikes in uranium.

Because it takes time to explore for, find, approve, develop and produce uranium, there is an excess profit opportunity for those who can bring uranium supply online quickly.

It’s not just uranium though. Different forms of energy creation require different combinations of resources. Understanding which energy mix we are moving towards means that you can predict how demand for those resources could shift.

Nuclear power uses far more chromium and nickel than other green sources of energy, and far less zinc and silicon than wind and solar. This may present an additional way to play the nuclear reactor construction boom.

Things to keep in mind about uranium stocks

One of the key benefits of nuclear power is its highly predictable needs. Because of this, nuclear power utilities tend to use very long-term contracts when it comes to uranium supply. That is why anticipated deficits in the long-term future can mean decent profits in stocks now – they may be able to secure the contracts ahead of production.

Paladin’s CEO told a conference that “Term contracting volumes are on the rise. What’s held back the uranium industry for the last decade was a lack of term contracting … [which] has been well below consumption [since 2013].”

This means stockpiles are being exhausted. Paladin estimates a 40 million pounds per annum deficit for the next decade. That demand must be met. Production must begin again soon.

Is nuclear the only answer?

Before we explore how to profit from the shift to nuclear power, I want to leave you with one last thought. Given the ability to secure and store vast amounts of fuel for nuclear reactors economically, I have always asked this question: why stop at 25% of the UK’s energy supply? Why not go to 100%?

For all other forms of energy, diversification makes sense to me. Oil and gas need to be imported, which means that supply can be disrupted and storage is expensive. The wind doesn’t always blow. The sun doesn’t always shine.

But I simply don’t understand why nuclear is only part of an energy mix instead of the entirety of it. The cost savings of doing away with a variety of other options would be immense.

If France can achieve 70%, thereby leaving Germany and its Energiewende in the coaldust every single day of 2022, then why not go to near 100% baseload, carbon neutral, cost effective, controllable power?

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor-in-Chief, The Fleet Street Letter

How best to profit from the Nuclear Renaissance

|

In early December a nuclear breakthrough was made at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

For the first time, positive net energy was released from a nuclear fusion reactor. That’s the same kind of reaction that takes place in the sun.

That’s big news. Fusion energy is no longer conceptual. We now know it can be done. The wrinkle is it will be quite some time, perhaps decades, before the experiment is commercialised.

In the meantime, we have an urgent need for new electricity generating capacity today. For one thing, many of the power plants built in the 1970s are reaching the end of their anticipated life spans.

The war in Ukraine has highlighted to everyone the dangers of relying on imported energy. What most people fail to realise is how dependent on Russia we are for enriched uranium.

On top of that, the success of the green lobby in shaping energy policy means that coal is being cut out of the energy mix.

The drive towards carbon free transportation is creating demand for batteries. Electricity supply needs to respond.

There is a critical need for baseload electricity. That is a powerplant which can supply electricity on a 24/7 basis. In the context of this edition of The Fleet Street Letter, that means a plant that does not rely on the weather to produce electricity and still meets carbon emission rules.

The only way to do that at scale today is with nuclear power. The range of possible solutions is increasing all the time. The most promising are small modular reactors. These are next generation designs that will fit on container trucks and that can be manufactured on a production line.

XXXXXXXXXXX is currently selecting sites to build a production line for small modular reactors in the UK. The company estimates building 16 of these devices in the next decade.

South Korea’s Doosan Enerbility is already producing the components for small modular reactors and expects to deliver to its first customers soon. It is working with Saudi Arabia on its SMART design, with the United States on NuScale’s design and will also supply XXXXXXXXXXX with components.

Several companies are in line to build small modular reactors. So what kind of fuel will they use?

At present, the EU imports enriched uranium fuel for its nuclear plants from Russia. Rosatom supplies 38% of the global market for this product.

To date those imports have been free from sanctions. However, both Poland and Lithuania are lobbying for them to be included in the next round of sanctions which will mark the 12-month anniversary of the invasion on 24 February.

Hungary is opposing the effort to sanction Rosatom because it has a nuclear plant it wants to expand with the company’s help.

Nevertheless, it is worth remembering that we are in the middle of winter. The war is not making as many headlines today because it is hard to fight when temperatures are so low. When the spring arrives the ferocity of fighting will pick up and pressure for additional sanctions will return.

Buy the right part of the fuel cycle

I am bullish on uranium and uranium miners, but the strategic play today – I believe – is to buy an enricher of uranium fuel. I am focusing my attention on the production of fuel for small modular reactors as well as for conventional reactors. At present there is only one company that is aiming to do both.