In this issue:

- China is hoarding copper: what is it up to?

- Why copper is the backbone of the energy transition

- Access to copper is becoming an economic imperative

Something strange is going on in the copper market, specifically in China.

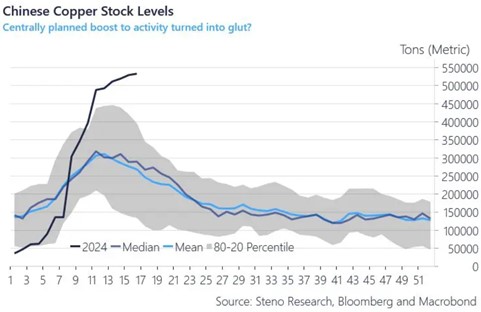

Starting mid-February, China started to hoard copper like there’s no tomorrow, as the chart below shows.

Although inventories usually grow around Lunar New Year at the end of January – as Chinese smelters keep working through the holiday period but many factories reduce their operations – this year the build-up has been the most pronounced since 2020.

Interestingly, despite the large build-ups in warehouses, imports have also risen over the same period.

It’s hard to say for sure what China is up to, but it certainly is unusual.

China typically uses its stock of copper this time a year but instead it is building stock, all whilst the price of copper surges. So what’s going on?

As noted by Andreas Steno Larsen of Steno Research, one argument is that the stock levels are building as a consequence of sluggish demand but another is that China is potentially looking to get ahead of further copper price rises as it builds out massive capacity within green tech, be it in solar panels, electric vehicles (EVs) or wind turbines.

China’s domestic economy, after all, has pivoted away from focusing on property development and tech to massively ramping up its production of green technology.

Certainly, this argument gains credence in light of last week’s announcement from Washington of sharply increased US tariffs on Chinese goods, including EVs and solar panels.

If Beijing had prior forewarning of the tariffs, then a power grab on global commodity supply chains including copper makes sense.

After all, copper is the backbone of the clean energy transition.

Millions of feet of copper wiring are needed to build the more complex grids that can handle electricity produced by renewable sources and balance out their intermittent supplies.

Solar and wind farms, specifically, are often spread out over large areas, meaning they require more copper per unit of power produced than do centralised coal- and gas-fired power stations. Meanwhile, EVs use over double the amount of copper as gasoline-powered cars do, according to the Copper Alliance.

So it makes sense that China would want to tighten its grip on supplies. China’s strategic stockpiles help it to influence prices on global markets and protect against shortages for its domestic industry.

But with similar stockpiling taking place in other commodities such as oil and iron ore, could China also be preparing for a structural devaluation of its currency, stocking up on important commodities in advance?

Remember, the Chinese economy has remained sluggish post-Covid so giving a boost to exports through a devaluation of the yuan could support the manufacturing sector, not least within EVs, solar and batteries. These industries would certainly gain momentum from a one-off CNY devaluation.

Certainly, a weaker currency would also help alleviate deflationary pressures.

What’s more, severe yen depreciation is also making Chinese exports uncompetitive globally, strengthening the case that China could be about to devalue the yuan. The Japanese currency is now at its lowest against the US dollar since April 1990.

Though there are also compelling reasons why China won’t turn to such a move – it could trigger capital outflows and add fuel to the fire in trade tensions with the US and EU at a time when China is running a 5% trade surplus – a one-time yuan depreciation can’t be ruled out.

It would certainly spell good news for commodities across the board.

Although copper has certainly rallied in recent months, fuelled by bets on looming shortages as mines struggle to meet rising demand from EVs, grids and data centres, there is a lot more left in the trade.

Quite simply, there isn’t enough new investments in copper mines, which take many years – even decades – to build.

We can certainly view BHP Group’s recent proposed $39 billion takeover of Anglo American as an indication of the difficulty it is to develop new copper projects, part of a larger trend of mergers and acquisitions as metal producers look to buy rather than build production growth.

Despite projections of a ramp-up in demand, production from existing mines is set to fall sharply in the coming years.

Many mines around the world are nearing the end of their lifespan and the quality of the ore is in decline, meaning more is needed to achieve the same standard.

The closure of a copper mine in Panama and a lack of new projects in the pipeline suggest supplies are set to shrink, according to Ewa Manthey from Dutch bank ING.

“If we don’t find new copper deposits or they are not brought online quickly enough, then we’re going to see an extended supply deficit. This would lead to higher copper prices over a longer timeframe,” says Manthey.

According to estimates, miners will need to spend more than $150 billion between 2025 and 2032 in order to fulfil the industry’s supply needs – so all roads point to an impending supply crunch.

Indeed, Goldman Sachs expects demand to outstrip supply this year.

“The combination of record low copper stocks [globally], our expectation of peak mine supply next year, rapid green demand growth, and low price elasticity of both demand and supply will in our view lead to copper scarcity pricing in 2025,” analysts at Goldman Sachs said in a recent note.

Historical precedent suggests prices could surge by 25% over the next 12 months, its economist said.

No wonder countries such as China are jostling to secure supplies. Access to copper is quite simply becoming an economic imperative.

Whatever China is up to, its ongoing purchases of copper will only serve to boost select commodity prices.

Readers of Strategic Energy Alert recently learnt of a way to play the spike in copper and another commodity enjoying its time in the sun. Click here to find out more.

Until next time,

James Allen

Editor, Strategic Energy Alert