In today’s issue:

- The US stock market is dangerously overvalued

- Mean reversion is not known for its kindness

- What will replace the US’ extraordinary bull market?

Financial markets have always controlled governments. Just ask Liz Truss or Matteo Salvini how. Or recall this exceptional speech from former MEP Daniel Hannan in 2009, reading Prime Minister Gordon Brown his tea leaves:

“Our currency has devalued by 30%. And soon the voters too will get their chance to say so. They can see what the markets have already seen. That you are the devalued prime minister of a devalued government.”

That was itself an echo of John Smith telling Prime Minister John Major and Chancellor Norman Lamont the same in the wake of Black Wednesday.

Reminiscing about this sort of schadenfreude may be good fun. There’s nothing like a bad government getting what it deserves from capitalism’s accountability mechanism.

But it’s less amusing when your own money is at stake.

Today, we look at the future. Because 2025 is shaping up to be a terrible year for the US stock market. And thereby its incoming president, Donald Trump.

But not for the reasons you might be used to.

What goes up must come…

The US stock market has utterly dominated its peers around the world for a decade. In fact, the surge in US share prices has left other major markets for dead. It’s difficult to overemphasise just how big the gap in performance has grown over time.

This chart shows how the returns on US stocks have blown out to absurd levels relative to European shares.

From July 2014 to June 2024 the US-focused Vanguard Total Stock Market Index (VTSMX) returned 12.0% per year. The non-US focused Vanguard Developed Markets Index (VTMGX) returned just 4.6%. That’s a staggering difference of 7.4% per year, with US stocks rising 1.6 times faster!

Not only is the outperformance vast, it has been surprisingly plain sailing along the way. State Street Global Advisors calculated that US stocks have been a better bet for a record 134 consecutive months.

Adjust for exchange rates and that rises to 180. “In fact, every rolling 10-year period from 2013 onward has favored US equity markets,” State Street concluded.

The same goes for every single developed country you might compare the US stock market performance to.

This extreme outperformance of one country’s stock market has caused some bizarre statistics to start popping up.

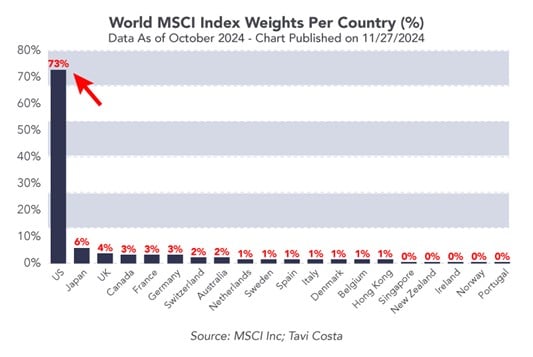

For example, you can compare the value of the companies in the US’ S&P 500 index to the size of the global stock market combined. The US’ share has risen from around 35% in the 1990s to more than 70% today! Next highest is Japan, at around 6%, and the UK has 4%…

All this is extraordinary. But what makes it all the more remarkable is how it happened.

Why are American profits worth more?

If US companies had performed better in terms of profits or dividends, it would make sense for them to outperform on the stock market too. Then American shares would’ve been worth more objectively speaking.

But the financial data firm Morningstar pointed out that it wasn’t really company profits driving the divergence. Past and expected future profits are not that different compared to other developed countries’ stock markets:

The long-term historical earnings growth (past five years) of foreign developed-markets stocks did trail that of US stocks. However, the difference was minor: 5.5% versus 6.3%.

And while analyst expectations for future earnings growth (three to five years) also favored US stocks, it was also only by a relatively small amount: 11.7% versus 10.7%.

Such small differences cannot explain the dramatic outperformance of US stocks. In other words, US stocks’ outperformance is mostly explained by rising valuations.

This means investors were willing to pay more for the same profits in the US than elsewhere. They bid up the price of equivalent stocks to much higher levels in the US, making them expensive relative to their value.

Measures of such valuations have reached extreme levels in the US, while remaining suppressed elsewhere. Morningstar summarised the gap in valuations:

- Price/earnings ratio of US stocks was 52% higher

- Price/book was 131% higher

- Price/sales was 85% higher

- Price/cash flow was 57% higher

So investors are paying vastly higher prices for the same pound of profits in the US than in Europe, Japan and Australia. The same for accounting values, sales revenue and cash on the balance sheets too.

Most absurd of all, the dividend/price ratio of foreign developed-markets stocks was 120% higher. This means investors value US dividends 120% more than non-US dividends.

This sort of divergence should not occur. It’s absurd for a dollar of profit or dividend to have a dramatically higher price in the US than outside it.

Mean reversion is not known for its kindness

Historically speaking, expensive stocks tend to underperform while cheap ones outperform. That’s the basic premise of value investing – Warren Buffett’s famous methodology. You should buy what’s cheap and sell what’s expensive.

This implies that non-US developed market stocks should dramatically outperform US stocks in coming years. Probably by way of a plunge in the value of US stocks. Investment strategist Albert Edwards put it like this:

This is getting silly. US share of MSCI world index is circa 75% […]. But old hands will remember the late 1980s when Japan was circa 50% of the world index. Japanese companies and especially banks dominated the world. No-one could conceive it would end, but it did.

Japan’s stock market bubble burst in dramatic fashion, to say the least. Here in Japan, it’s still rude to mention stocks. Too many people had family members commit suicide when their portfolios blew up in the 1990s. I found that out the hard way.

But every time investors around the world bet on a return to normality by selling their American shares and buying non-US stocks, the gap just grew even more.

As the Economist magazine asked, “Should investors just give up on stocks outside America? No, but it’s getting a lot harder to keep the faith.”

Reversion to the mean will strike back… eventually

It’s unlikely the US stock market can sustain its outperformance much longer. What goes up must come down and one sector of the market cannot leave all others behind indefinitely. That was true of Japan in the 90s, tech stocks in 1999 and countless other bubbles.

At some point, reversion to the mean must kick in as investors go shopping in cheaper markets outside the US. They’ll get more bang for their buck in terms of dividends and profits, which should define long-term returns.

So, the big question all investors face today is simple: where to invest?

Today, we stake our claim on the sector we expect to outperform in 2025.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor, Fortune & Freedom