- Suddenly, elections could matter to the European Commission

- The next schism of the Holy Bruxellian Empire

- Populist panic will infect the EU in 2024

With the European Parliament elections coming this June, I thought it’s time to dig out the analysis that convinced Nigel Farage to work with me on Fortune & Freedom five years ago.

Despite the absence of Nigel’s rather large contingent of eurosceptics, the upcoming European elections offer the first real chance of functional opposition to the European Commission’s flood of directives.

As John Butler explains here, if enough eurosceptics are elected, the European Parliament could become a genuine roadblock to the Commission rather than just a rubber stamp. Europe’s inherently undemocratic institutions may yet get swamped by sufficient votes for the first time.

But why is this on the cards at all?

That’s what I predicted back in January of 2019…

***

The Populist Reformation

And the schism of the Holy Bruxellian Empire

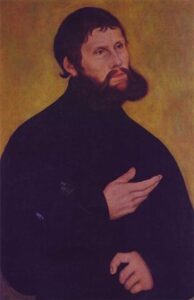

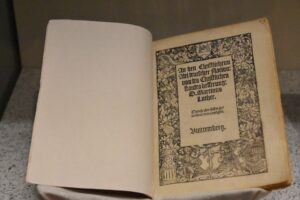

502 years ago, Martin Luther nailed his ninety-five theses to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg. As you probably know, he got into quite a bit of trouble as a result. And eventually split a largely unified Catholic Europe into many pieces.

But there’s a particular part of Luther’s story I want to focus on. Think of it as the true story of the Reformation. It involves the unfortunately named Diet of Worms and Wartburg Castle.

The Diet of Worms was the imperial general assembly of the estates of the Holy Roman Empire. The European Parliament of its day. It was held in Worms, Germany in April 1521. Luther was ordered to appear and answer for his banned theses and other writings. The Diet decided on Luther’s fate as an outcast after he refused to recant.

|

On his way back from the Diet of Worms, Luther was kidnapped as planned. But not by his enemies.

Frederick the III, Elector of Saxony, was behind the plot. His horsemen put on masks and pretended to be highwaymen. Or a band of knights, depending on who is telling the story (I’m not sure you could tell the difference in Germany at the time).

The gang disguised Luther as one of them under the alias Junker Jorg. They took him to the safety of Wartburg Castle, from where Luther continued his work. He famously translated parts of the bible into German there.

Now we get to the controversial part of my own theses. The history of the Reformation is not about religion. At least that is not the key to understanding what happened.

Europe’s Reformation of the 1500s was about politics and communications technology. About nationalism and the printing press. About Germany rejecting Europe’s Catholic Holy Roman Empire, and having the power to do so.

|

I’ll prove it to you in a moment. But first, why should you care?

Because exactly the same process is currently underway again in Europe. A second Reformation has begun. A second rejection of a European empire. A rejection empowered by another revolution in communications technology.

As soon as you recognise the Reformation for what it truly was, you’ll begin to see the similarities to today. And thereby you’ll be able to predict what’s about to happen to the Holy Bruxellian Empire.

Last time around, the Reformation created an almighty mess. This time around, I think you need to be prepared for serious civil unrest in the streets, economic and financial crises, and social upheaval. The sort of thing you can already see on the news in France. The sort of thing you’re worried about if there’s a second Brexit referendum.

In short, it’s going to be an incredibly difficult time to try and build your wealth. Or even protect it.

But in this newsletter, that’s we aim to do. Forewarned is forearmed, so let’s dig in.

The protestants were the populists of the 1500s

Today, Luther’s Reformation is presented as a religious conflict. But at the time it took place, and given the forces that made it take place, the real conflict was clearly between national and imperial politics. Between nationalism and European unionism. Just like today.

The word “protestant” was originally a political declaration, not a religious one. “Protestant” described states which rejected the Edict of Worms and Speyer, the imperial decisions that forbade anyone to support Martin Luther and join the Reformation. It was a question of sovereignty, similar to the “populist” countries of Italy and Hungary today, which reject the EU’s budget and immigration policies.

When a state turned protestant, they weren’t joining a religious revolution, but a political one. They were going against a political decision made by a political body: the Holy Roman Empire.

The political nature of the Reformation doesn’t end there. Nation and city states in Europe protected Luther and his fellow upstarts repeatedly against the authority of the Holy Roman Empire – not the Catholic Church. The kidnapping to Wartburg was just one example.

Rome’s enforcers didn’t dare go into many German cities to try and enforce their declaration – known as a Papal bull. They’d always relied on local political authorities to abide by and enforce imperial edicts. But local political resistance put an end to that.

Even when Luther was excommunicated, the Catholic Church already knew it wouldn’t be able to enforce its edict. The German city states and secular authorities had openly told them so in advance.

|

But why did Germany’s political powers revolt against the Holy Roman Empire? Well, by the time Luther came along, they were itching to do so.

The Gravamina and the creation of Germany

The idea of Germany as a nation was fairly new and still emerging during Luther’s time. Luther was a committed German nationalist who understood the political situation he began his Reformation in. Crucially, he understood it in advance. And he tailored his Reformation accordingly.

Luther’s writing specifically targeted the decision makers of the emerging nation of Germany. One of Luther’s most famous titles read “To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation”. It was that last bit which gave the title its controversial angle.

Dean Messinger from Loyola Marymount University explains:

Luther saw how the newly created nationalistic views, matched the demands for clerical reform, and would use a backdrop of national identity, and make an explicit appeal to the national powers and to the pride of the Germans, as a means of swaying secular rulers to his cause.

Two years after publishing To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, the German nobility responded by publishing the Gravamina. Think of it as the German version of the Magna Carta. It was a list of grievances that the German nobility had with the Catholic Church in Germany. But its real message was for the Holy Roman Empire.

The German Christian nobility saw Luther as the spiritual backing they needed to put their political plans into action. They’d already been agitating about a German nation for decades. Especially with the trade in indulgences sucking Germany’s coffers dry at regular intervals. Luther also complained about the other taxes Rome levied on German states.

As Luther wrote, “Now that Italy is sucked dry, they come to Germany and begin very quietly; but if we look on quietly Germany will soon be brought into the same state as Italy”. It sounds like the EU’s political debate today.

The first eurosceptic

In his religious writings, Luther carefully dismantled the pope’s claims that he was the political authority in Europe, that his power over secular states was absolute. And Luther was far from the first to combine nationalism with Catholic Church criticism, especially in Germany.

The Reformation, as it unfolded, was state led. It was about governments establishing their authority against the Holy Roman Empire, without having to abandon religion at the same time.

In fact, Luther’s rescuer after the Diet of Worms never converted from Catholicism. The aforementioned Frederick III owned one of the biggest collections of relics around, entitling him to a huge collection of indulgences. He clearly backed Luther for political gain, not religious reform.

The primary reason Luther’s opponents in Germany resisted Luther was also political. Small German city states usually favoured Luther’s religious reforms and nationalism. But they had traditionally relied on the Holy Roman Emperor for protection from the more powerful German land-owning nobility that surrounded their cities. The Reformation called for everyone to take sides on the political divide, not just the religious one.

Among the peasants and free men in the cities, it was much the same. Author Andrew Pettegree put it like this:

In the years before and after the dramatic confrontation with the emperor at Worms in 1521, public interest in Luther as the symbol of national resistance to an alien authority far outstripped any public understanding of his theology.

But what made Luther’s German nationalism tear through Europe like a brushfire where others had failed? That’s easy. The printing press.

Information revolutions trigger political revolutions

Until Luther, printing was a miserable business. Many printers had gone bust over the six decades since Gutenberg invented the press. The moment the printing industry met Luther was the moment it boomed.

Printers across Europe turned Luther into the all-time most published author in Europe. Within just five years of his theses being nailed to the church door, too. That’s how the Reformation began. It’s also what made the Reformation possible.

But what made printing so powerful?

There are plenty of obvious answers. Like the cost savings printing created. You can read about the rapid spread of the Reformation pamphlets elsewhere. My point here is much more simple and specific. It’s all about speed. Relative speed.

Luther’s success, and the success of German nationalism, rode on the back of an invention that enabled faster communication and dissemination of information than the authorities could keep up with. This gap in speed is central to the story of the 1500s, as it is for Europe’s Populist Reformation today.

Luther was able to churn out many pamphlets that were printed and reprinted across central Europe before the authorities were even able to figure out what to do about him. By the time they’d decided, the German population, and especially their leaders, were in a position to dictate terms. The Reformation had passed Catholic Rome by before they even knew it was on.

In other words, by the time the church caught up, they’d lost the capability of enforcing their rulings. The speed and power of the printing press devastated the long-established power balance of the day.

The end of censorship

Apart from the obvious reasons, the printing industry was so effective and fast in Germany because of its decentralised structure. Even when printing Luther’s pamphlets was banned in some cities, they were just printed elsewhere. The internet is the same today.

Leipzig went from being Germany’s top printing centre to a backwater of the printing world after banning Luther’s works. In Britain at the time, printing was centralised in very few places, allowing a ban on Luther’s works to be effective.

The printing press’s ability to scale up is another key factor. Printers would simply print their own versions of copies that fell into their hands. Often, the later printers’ copies were better as they had to improve the design to compete at the bookseller. But the point is, this allows exponential growth in the amount of copies available. And it is nigh impossible to censor the pamphlets effectively.

The last point I want to make about the printing press, and the way it was used by Luther, is perhaps the most important. Luther favoured short pamphlets of about eight pages, written in simple German. Think of it as blogging today.

Luther’s pamphlets broke the Catholic Church’s monopoly over much more than religion. Luther’s pamphlets destroyed the church’s political power by making priests less influential. They had been key the sources of education, news of world events and guardians of public opinion.

But with Luther’s pamphlets in circulation, they could no longer effectively monopolise that information or power. Censoring the spread of ideas became impossible. And people discovered alternative ways of interpreting world events.

Today, the news media is being phased out in much the same way. TV stations and newspapers used to control what people knew, how they thought and how they voted. Today, they’ve largely lost that control to the internet.

The Protestant Reformation is the prime example of how information revolutions trigger political revolutions. But the same thing has happened many times since.

The internet’s political power is proven

Nine years ago, Tunisian fruit seller Mohamed Bouazizi doused himself with gasoline and set himself on fire after his wares were confiscated by a municipal inspector. This moment triggered the Arab Spring of 2010. But how and why?

The Arab Spring revolutions of 2010 were often called the Facebook or Twitter Revolutions. Smartphones and social media played a crucial role in spreading information and communication. Word spread faster than authorities could react. And they had no hope of censorship.

Books smuggled into and out of the Soviet Union played a crucial part in bringing down communism. It took much longer for the effect to play out, but the nature of the effect was much the same as Luther’s writings. Authors revealed the horrors of what was going on behind the Iron Curtain through their books about the gulags. Some, like the most famous, Solzhenitsyn, were Russian nationalists.

These novels destroyed the Soviet Union from the inside and from the outside by undermining its moral authority. Just as Luther did to the Holy Roman Empire.

Compare these historical examples to the Gilets Jaunes (yellow vests) protestors today, and their use of the internet. Not just to organise rallies, but to spread their protest movement, and publicise it in the face of some media suppression.

Protest movements with the ability to communicate faster than the authorities can react are powerful. Especially if they are decentralised and therefore incredibly difficult to suppress.

And especially when motivated by the oldest rallying cry of them all – nationalism.

Europe today is ripe for a Populist Reformation

Luther wrote at a time when central Europe was very integrated under the Holy Roman Empire. With many smaller nations making up the whole. It was the European Union of its day.

Luther was a German nationalist as well as a religious upstart. He was so much more successful than those who came before him for a simple reason. He allied with the growing nationalist movement of Germany and gave it religious legitimacy. Suddenly the politics of German nationalism had spiritual backing. Protestants could break with the empire without breaking from religion.

A good chunk of Europe’s history goes on to be about the conflict Luther began. Nationalism and religious movements breaking away from European political and religious integration. The UK is an obvious example.

|

But I believe religion played a secondary role in all this. One that enabled nationalism by splitting spiritual and political authority apart. And that’s what really kicked off the Reformation.

The first thing I want you to realise this month is how similar events in Europe today are to the beginning of the Reformation. A time when the empire uniting Europe was built on a religious fervour that could not be questioned by anyone without the threat of excommunication.

Today we have the new “religion” of Europhilia – the worship of anything related to the EU, euro and Europe. It has infected Europe and anyone who questions it is branded a “populist”.

It’s worth mentioning, the opponents of Europhilia are often equally “religious”. Euroscepticism and nationalism are a matter of identity for many Europeans. They often can’t explain it, but are fervent nonetheless.

This month, I won’t take sides in this mess. Nor pass judgement. I’m not sure who is worse – the nationalists or the europhiliacs. But I am sure change is coming to the world around you. Just as it did in the 1500s.

***

The report went on to make many predictions. And outlined how investors could defend themselves.

Europe’s populist reformation has been steadily bubbling away since. All sorts of protests occurred, and more and more populists have gained power or influence. The AfD, Geert Wilders, Meloni and countless others are good examples. Large scale eurosceptic protests occurred too.

Although the pandemic threw a spanner in the works of this progress, it’s also clear that the response to the pandemic sped things up. So much government intervention was bound to trigger a backlash.

But I believe my piece from 2019 explained the underlying trend – the nature of what’s really going on in Europe. People want to take back control at a level they can hold their politicians to account. And I hope this issue of Fortune & Freedom helped make you aware of it.

If you’d like to be aware of the next revolution Europe faces, you’ll have to become a member of The Fleet Street Letter.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor, Fortune & Freedom