The last few days, we’ve been reviewing the idea of Currency Resets. And how they will impact your future.

We turned to the man who literally wrote the book on the topic, John Butler.

But I have a different take to John. Although we agree on what John has revealed so far, I believe Currency Resets are in fact far more common.

When John profiled the past Currency Resets, he turned to historical events like ancient Rome and the French Revolution. These were major Currency Resets.

Today, I would like to show you that the last 100 years have featured a sort of Currency Reset too. Rather often…

Which means, if another one happens soon, it should surprise nobody. That’s what I want you to walk away with today. But first, I’ve got to overwhelm you with evidence…

99 years of Currency Resets

Financial systems very rarely collapse completely. They’re reborn in a new form before the col- lapse unfolds. This usually occurs once the existing system has run its course – has maxed itself out in some way. Then it’s in everyone’s interest to reboot and start over with a new system, before the failure. And so that’s what governments do.

How does this happen? Every 21 years on average, during some sort of crisis, leaders of the world’s most powerful trading nations gather together at a gaudy location to hash out the new rules of the international currency and trading system. It’s practically a tradition at this point.

Only, at 34 years into the current currency system, we’re well overdue a reset. Mostly because the Americans had held on to their privileges under the current system rather tightly. Until they started abusing those privileges by printing infinite amounts of US dollars willy-nilly to keep markets afloat, that is.

Let’s review some of the Currency Resets of the past to get a flavour for what’s coming in the near future. That’ll help you understand exactly what a Currency Reset really is too.

Palazzo di San Giorgio, Genoa

In 1922, the first modern Currency Reset took place at the Genoa Economic and Financial Conference. Thirty-four nations gathered at the Palazzo di San Giorgio for what they called a “conclave”. On the agenda was the need to design a new currency system for international trade. They had to determine what would replace the gold standard which had fallen apart after World War I.

Under the new system – let’s call it the Genoa System – citizens could no longer redeem their government-issued banknotes for gold coins. Only untenably large gold bars were available to citizens looking to convert paper money into precious metals, as they were technically entitled to do. Central banks, however, could redeem currency for gold coins or bars, allowing for trade balances between nations to be settled in gold.

The effect was three-fold. To separate gold from the money we use day to day. To keep the gold of nations in the vaults of central banks, thereby safely backing the national currency. And to pre- vent citizens from being able to opt out of the national currency by redeeming and holding gold directly instead of national banknotes. In other words, it made us as citizens and traders dependent on the money of governments when we go about our daily business.

The agreement and its flaws set up the world for the roaring 20s. As well as Russia’s and Germany’s economic isolation and collapse. In fact, the Russians and Germans made their own separate monetary agreement out of spite…

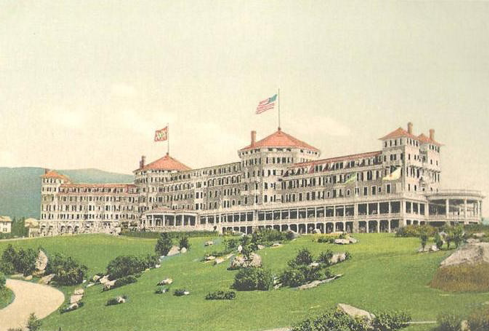

Twenty-two years and most of another world war later, the most famous Currency Reset in history occurred. You’ve likely heard the name. Well, part of it. The United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference took place at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, US. Very large books have been written about it, but let’s stick to what’s relevant here – the Currency Reset angle.

Mount Washington Hotel, Bretton Woods

While World War II still raged, 730 delegates from all 44 Allied nations met to hash out the new international financial order that would begin after the war. What they came up with is a little complex, but the fact that they did it is the key point.

Under the Bretton Woods System, exchange rates between currencies were pegged within 1% of each currency’s convertibility to gold. They did this in practice by pegging each currency to the US dollar and the US dollar to gold.

It’s a bit like all the carpenters agreeing to use the metric system, but actually using millimeters and not centimetres or metres in practice. Everyone pegs to the same measure, making millimetres the dominant number. Even today, just about every table and chair in the world is measured in both millimetres and US dollars in the end.

But why the US dollar? For an extraordinary reason. To spite Britain…

Before World War II, the British pound was an official and unofficial reserve currency in much of the world. Thanks to the British Empire and the Royal Navy, countries used pounds to conduct international trade. The Soviets and the Americans liked neither the British Empire nor the pound’s status. And so they sought to undermine both. Bretton Woods was their opportunity.

The US delegate to the Bretton Woods conference happened to be a Soviet spy with certain anti- imperial ideological leanings. Harry Dexter White faced off with Britain’s delegate John Maynard Keynes, who had suggested using the bancor as the global reserve currency – an arbitrary currency created for the purpose of the Bretton Woods peg.

Long story short, the Americans objected to Keynes’ plan and the US dollar became the global reserve currency instead. Just as Britain had before, and the Dutch before that, the US policed the US dollar system with its dominant navy – projecting power internationally and policing trade.

Both Genoa and Bretton Woods were dominated by the issue of war debts and how to deal with them given the constraints of gold standards. The currency system chosen focused on that problem. A similar problem to the one we have today – too much debt and too many financial crises. I wonder if our coming Currency Reset will look similar…

The next currency system was born out of the trade imbalances which fixed exchange rates under the Bretton Woods system created – similar to the issues I discuss in my book How The Euro Dies.

How the Bretton Woods system died

Bretton Woods fell apart when President Richard Nixon “temporarily” suspended the gold window in 1971 – exactly how the Genoa System and the gold standard that preceded World War I fell apart too.

If everything is pegged to dollars and the dollar is pegged to gold, but you can’t exchange dollars for gold any more, then the system simply doesn’t work. At least the French thought so, because they eventually tried to redeem the US dollars they’d accumulated for the US’s gold. Which is why Nixon closed the gold redemption window – to keep the gold.

The French leaders at the time saw the US dollar’s reserve currency status as an “exorbitant privilege”, for good reason. As American economist Barry Eichengreen explained, “It costs only a few cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce a $100 bill, but other countries had to pony up $100 of actual goods in order to obtain one”. This explains US trade deficits. And crucially, it’s true today too. With the Americans now printing money like mad, I wonder if our next Currency Reset will end this exorbitant privilege?

Nixon’s “temporary” suspension was designed to create time for another Currency Reset conclave. And that was held at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC in December 1971. The out- come is known as the Smithsonian Agreement – our third Currency Reset.

Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC

The next Currency Reset conclave was held at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. Under the system agreed to there, currencies were allowed to fluctuate 2.25% instead of just 1% as before. And the dollar was devalued against gold. But this fell apart so fast I’m not even sure it deserves to be on this list of Currency Resets.

What does count as a Currency Reset is what happened after the Smithsonian Agreement failed. Nation after nation abandoned the agreement’s fixed exchange rates in what amounted to the trade war of its day – they devalued their currencies. But the result was a new financial order – the era of floating currencies was born. A new international currency system. Suddenly, money had freely moving prices in foreign exchange markets – a novel idea.

But the floating currencies which sprung out of the failure of the Smithsonian Agreement created their own problems too. The US dollar appreciated 50% against major trading partners between 1980 and 1985, effectively making trade incredibly expensive for anyone but the US to conduct. (The same thing happened during the Covid-19 crash.)

To devalue the US dollar and restore order, the G5 finance ministers (the US, UK, France, West Germany and Japan) met at the Plaza Hotel in New York City in September 1985 for another Currency Reset.

Plaza Hotel, NYC

The Plaza Accord was to devalue the dollar against other key currencies to rebalance trade flows in a coordinated and cooperated way. It was market manipulation by a cartel of governments, but for a good cause.

But the central bankers and governments overdid it, triggering a collapse in the US dol- lar against the other major currencies. Not to mention the inflation and bust of Japan’s bubble economy. A year and a half later, the now G6 found themselves in Paris sorting out the mess of their previous Currency Reset.

US Dollar Index

Louvre, Paris

In the Louvre Accord of 1987, the G6 agreed to stabilise currency markets with an awkward in-between. Currencies would be allowed to fluctuate, but only so far. Like the Smithsonian Agreement, this failed and another era of floating currencies began. Except for the bungled European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) and doomed euro, of course. But let’s leave that for another book.

A board game with your (real) money

So, that’s 99 years of Currency Resets – conclaves of global leaders where the global financial order has been reset and the meaning of money in the new financial order hashed out.

Sometimes money is backed by gold, sometimes not and sometimes something in between. Sometimes money is allowed to fluctuate in value in the sense that exchange rates can move, sometimes exchange rates are fixed and sometimes something in between. Sometimes one nation’s currency is the global reserve, sometimes gold is and sometimes an awkward in-between of both. Sometimes there is a multipolar world order and sometimes one nation dominates.

The point is that the modern global currency system’s rules can be redesigned in all sorts of arbitrary ways. The definition of what is money often changes depending on what global leaders decide. Conferences to make those decisions happen every few decades and the last one was 34 years ago. Unless you count the creation of the euro and the breakdown of the ERM as further examples. Then we’ve hit 21 years – close to the average amount of years between resets.

Remember, each new currency system has flaws and consequences for financial markets and investors. I believe they set the trade winds that determine the direction of long-term investing success. That’s what explains gold’s outperformance of the stockmarket during certain eras, for example.

But what will the next Currency Reset look like? And when will it occur? My friend Sam Volkering thinks he knows the answer. Find out what it is here.

Nick Hubble

Editor, Fortune & Freedom