- When Hayek grabbed inflation by the balls

- How inflation swindles the equity investor

- Why we didn’t get inflation after QE1, QE2, …

I’ve copped some flack from readers for claiming that anyone correctly predicted our inflationary burst of 2022. Not to mention that it was a deliberate policy from governments and central banks. Surely that’s just a conspiracy theory…?

It certainly doesn’t gel well with European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde’s claim that inflation came from “pretty much nowhere”. Then again, she was the source of the inflation. And she has been criminally convicted of financial negligence before…

Regardless, I did explain back in July of 2020 precisely what was about to happen. Not to mention how, why and what it would mean for you…

***

Euthanise the rentier

How you will pay off Britain’s Covid-19 debt

In 1976, the Austrian free market economist Friedrich Hayek made a visit to Australia. He’d been invited by a group of people, some of whom I know personally today. During this trip, he went to the Atherton Tablelands in North Queensland to see one of his host’s cattle farming properties.

Ron Kitching, the Mont Pelerin Society member, mining industry legend and cattle farmer later recalled the visit like this:

[Hayek] noticed hanging on the wall of the bar, a large picture of a magnificent Brahman Bull I owned. He asked about the Bull, so I told him he was a prize winning show bull which I had nicknamed Inflation as he would not stop growing. “He weighs 3,000 pounds in his working clothes,” I told the small gathering present.

“Well, while I am here, I would like to meet him,” Hayek exclaimed. So I put that on the agenda.

I got this bright idea that I’d put the bull in the yard, get a step ladder put Hayek on the bull, (if he agreed), and take a picture which would carry the caption Hayek’s on Top Of Inflation. I told my wife and that was the end of it. She would not under any circumstances countenance such a move. “What if the Professor fell off and was injured?” So that project was abandoned.

Nevertheless Hayek still wanted to meet the bull. Next day I took him down the paddock and took several pictures of him and the bull when another idea popped into my head and I quietly mentioned it to him. He was delighted to have a bit of fun. The caption of course was to be Hayek’s Got Inflation By The Balls.

Well the old boy was delighted. He was quite at home with animals and had palled up with the bull, which was an easy matter with this particular animal. So he posed and I took the picture. He predicted that if the Americans got hold of a copy, the picture would become famous.

This photo became so famous in fact that, years later, none other than Margaret Thatcher was presented with a copy of it. The photo shows her economic adviser and intellectual hero grabbing inflation by the balls, literally. Apparently she liked it. I’m not sure what Inflation thought of it, but he looks nonplussed.

Source: Ron Kitching

Source: Ron Kitching

With help from Hayek’s economic theories, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volker’s persistence and Thatcher’s balls, inflation was eventually brought under control in the UK and US. And it has stayed that way ever since, with more fear about deflation and the bear market it threatens.

But this month’s issue is designed to prepare you for Inflation’s revenge. Because politicians and central bankers have grabbed Inflation by the tail instead of the balls, in the hope it would drag economies out of deflation.

But now they can’t let go without getting gored. Which means we’re in for one hell of a ride…

Inflation is back, with a vengeance

There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.

– J.M. Keynes

I don’t think there’s much value in us discussing what inflation can do to an economy, to a society and to a country. It’s not exactly controversial stuff.

And many of you likely remember Britain’s last inflationary period. Or know about the scars it left on your family when you were young. Ironically, my auntie recalls it as “when money was tight”.

Inflation’s effect on the bond market, where much of Britain’s pension assets are invested, is of course disastrous. The only thing worse than cash during inflation is the promise to be paid cash in the future. “Bonds have once again become certificates of confiscation” claimed market historian Russell Napier recently.

He’s one of two financial heavyweights (the other being Albert Edwards, who we’ll get to shortly) who inspired us to stick our neck out this month, with a prediction of inflation. The two are especially noteworthy because they correctly predicted the prolonged deflation of the last decades.

But both have recently come out with predictions of inflation, swapping sides in one of the great economic debates of the last few decades. That’s an extraordinary turn of events for anyone who has followed their research and books, as we have.

Back to that below.

First, there is a great deal of value in reminding you of what inflation does to the stockmarket specifically. Because there are many misconceptions about this. Dangerous misconceptions you can’t afford to have any longer.

How inflation swindles the equity investor

Warren Buffett, writing in Fortune Magazine in 1977, at the height of this inflationary boom, explained what was going on. He called the article “How Inflation Swindles the Equity Investor”:

It is no longer a secret that stocks, like bonds, do poorly in an inflationary environment. We have been in such an environment for most of the past decade, and it has indeed been a time of troubles for stocks.

For many years, the conventional wisdom insisted that stocks were a hedge against inflation. The proposition was rooted in the fact that stocks are not claims against dollars, as bonds are, but represent ownership of companies with productive facilities. These, investors believed, would retain their value in real terms, let the politicians print money as they might.

But stocks went down, in real terms (meaning adjusted for inflation).

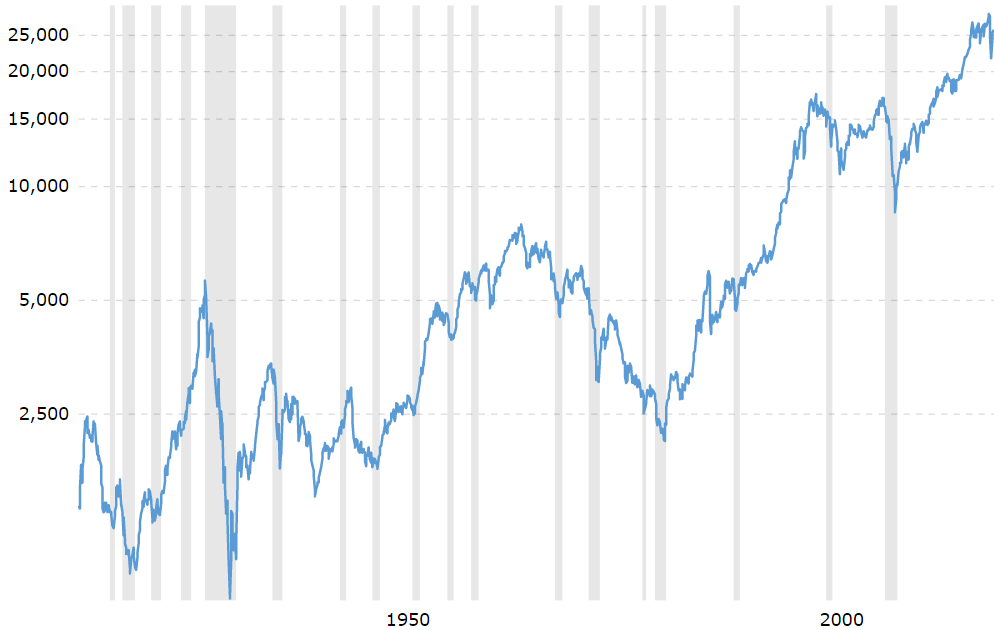

This extraordinary chart shows the awesome power of inflation to trash the stockmarket. It shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average, inflation adjusted. As you can see, the bear market of the 70s, which was driven by the falling value of money instead of stocks actually falling, took the US stockmarket back to the level it reached in 1915! This despite the DJIA actually rising 10 fold in nominal terms during that time.

Inflation-adjusted DJIA

Source: Macrotrends

Source: Macrotrends

It reminds me of a hamster wheel. Investors made huge capital gains during that time. But when they sold their stocks, right up to 1982, they discovered the price of a loaf of bread and a pint had risen more than their stocks had. And then there was the tax man to pay off first, after having made an epic, if theoretical, capital gain.

I think this makes the stakes of this monthly issue painfully clear. We’re talking about the prospect of a bear market in stocks, in real (inflation adjusted) terms. Likely for many years or even decades to come. The stakes couldn’t be higher for investors. Especially with the alternative – bonds – faring even worse.

So, I better explain what has led us to predict inflation. Especially given this isn’t my first time doing so…

Why we didn’t get inflation after QE1, QE2, QE3, QE4…

The first waves of quantitative easing (QE) were released in 2008. At $700 billion, it was scandalous at the time.

The vast money printing effort triggered an even larger deluge of apocalyptic warnings about how it would lead to inflation. “This is what the Weimar Republic did,” pointed out all the critics. “John Law would be proud,” I probably wrote. And Gideon Gono, the former head of Zimbabwe’s central bank, suddenly found himself a valued expert on monetary policy.

But that inflation never emerged. At least, not in consumer prices.

In fact, we’ve had some of the lowest inflation ever recorded during periods of QE. Right now, inflation expectations are hitting extreme lows. In France, expected inflation over the next four years recently hit its lowest level ever of 0.14%. This is measured based on the gap between inflation protected bonds and normal bonds.

Other nations are close to their all-time lows of 2009 by the same measure. In the US, we recently saw three consecutive monthly declines in core CPI, which is extremely rare. Strangely, in the UK, we have a comparatively high expected inflation, possibly because of Brexit’s devaluation of the pound.

But pointing out the lack of inflation from QE is a little misleading given the causation runs the other way around. QE is used when inflation gets too low. Medicine is used when you’re sick, but that doesn’t mean it makes you sick.

But it is still remarkable how wrong the inflationist doom mongers have been. Including, for that matter, me. Trillions of new dollars, euro, yen and pounds have landed us here, with extremely low inflation and inflation expectations.

The deflationists who ridiculed us all along had made the most of repeating “I told you so”. But recently, something changed. Leading deflationists have swapped sides. They’re warning about a return to inflation. And it won’t be a good thing…

Crossing the Rubicon into inflation’s paddock

Recently, central bankers and politicians crossed a Rubicon, meaning they cannot go back. And they’ve crossed into Inflation’s paddock, unleashing a hugely powerful and dangerous force.

But how exactly? What is different this time?

Well, as the renowned deflation predictor Russell Napier puts it, they have “seized control” of the money supply in a more direct way. Not with QE, but by forcing bank lending, sovereign bond monetisation and even action within corporate bond markets.

Here’s the key claim in a nutshell: The level of government and central bank control is now so direct and immediate that inflation will finally emerge.

But what control are we talking about?

Well, until now, banks have not been forced to lend out the money that central banks pumped into them. In fact, one of the big problems facing policy makers who tried to fight deflation was that banks did not lend the money which the central banks were dishing out. They hoarded it instead.

But the Covid-19 crisis has changed that. The economic programs you’ve seen around the world interfere to such an extent that governments can now mandate lending – the crossing of the Rubicon.

Money is on the move

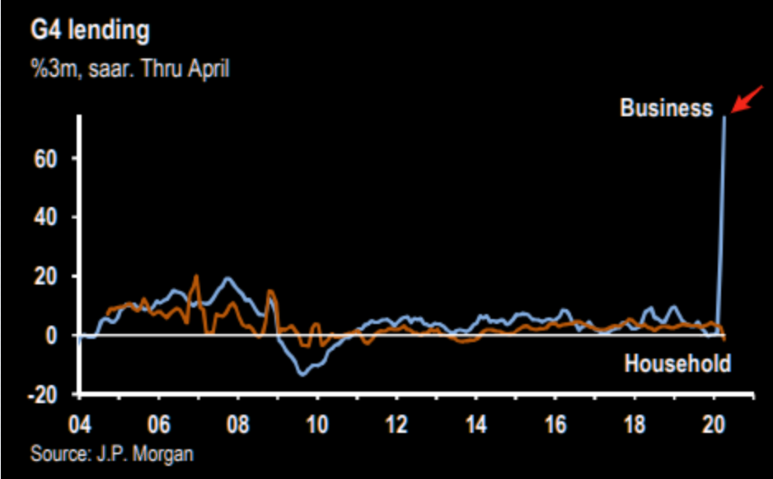

This chart shows business lending amongst the G4 economies. It is telling you that borrowing by business has exploded, to put it mildly. Compare this to 2008, when business lending crashed from what was a high level at the time.

This boom in lending is a combination of emergency drawdowns of pre-agreed credit lines by struggling businesses and government backed lending programs. “We are witnessing […] the fastest expansion of bank credit into a recession, ever [in the US]” explained Napier recently. Programs like the UK government’s “Bounceback loans” have forced money into circulation.

And the result can be seen in the money supply too:

Why didn’t this boom in the money supply happen during previous periods of QE?

What you need to understand is that the money supply is far more reliant on bank lending and government spending than it is on central bank money printing.

Most money is lent into existence by banks. When you spend money on your credit card, that money doesn’t come from somewhere, it is created in the process of the transaction. This means that the money supply is a fickle thing, reliant on bank lending and borrowing by consumers, governments and businesses. And, with the government heavily influencing bank lending, they now control the money supply more than ever before.

With this newfound control of the money supply, governments really can engineer inflation at last. We’ll get to why they want to in a moment.

But will this continue after the pandemic is over?

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program”

As the economist Milton Friedman explained, “Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program”. After the bounceback loans will come the normalisation lending programs. And then we’ll have the green new deal. And so on and so forth.

In fact, as we finalised this month’s issue, Boris Johnson announced his own New Deal to get Britain back on track. The spending boom will have to be debt funded, sending the money supply surging. The austerity that held back inflation in the past will be replaced with inflationary over-spending.

Perhaps the best-known deflation predictions over the years have come from Société General’s Albert Edwards. In the face of vast QE, he didn’t budge from his famous Ice Age hypothesis of steady deflation.

But now he’s flipped to the inflation camp too. And his explanation for why sums up our message this month: “this economic bust is so serious and so deflationary that policymakers felt they had no choice but to cross the policy Rubicon. Indeed we will see more and more stimulus until the deflationary ice melts.”

But why? Why do policymakers want inflation so badly? Isn’t it bad?

And why won’t central bankers simply raise interest rates and stop printing money, to bring things back under control?

For a simple reason…

***

Which I’ll reveal in part two, tomorrow.

But first, don’t forget just how unpopular discussing inflation, let alone predicting it, was back in July of 2020. In fact, I was roundly lampooned – the boy who cried “wolf” and all that.I can only say that I’m rather grateful to be given the helm of The Fleet Street Letter – a place where I can publish such predictions. It’s not that I fear being ridiculed, it’s just that few publishers would entertain views that go against the consensus quite so blatantly, whatever the track record of being right may be.

Perhaps you appreciate hearing such views? If so, click here.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Editor, Fortune & Freedom