I expected to write this article about Brexit’s risky implications. But it’s become about Covid-19 instead. Still, the underlying topic is the same: how will we govern ourselves after 2021?

You see, Brexit in and of itself doesn’t change the laws we’re governed by. Instead, it merely changes who makes and changes our laws. Whether it’s European politicians in Brussels, or British politicians in Westminster – that’s all Brexit decided.

Now I’d argue, for a long list of reasons, that British politicians in Westminster are slightly more likely to do a better job of governing the UK than European politicians in Brussels. And I mean that – slightly.

You might think the difference is huge, which is fair enough – I’m not going to argue about the magnitude today.

But why do I believe UK politicians are better at governing the UK? Because their incentives are more aligned with doing so. And that’s the key – incentives.

The problem with governing ourselves as an independent nation, at last, is that Covid has radically changed how we will govern ourselves. The vision which Brexiteers had in 2016 of a self-governing and independent Britain has expired. And I don’t like what’s replacing it, post Covid.

I’m not just talking about lockdowns, quarantines, tracing apps, Covid passports or any other government measure. But the longer-term consequences which Covid brings up which may involve far more encroachment and Covid like policies in the future.

Just when Brexit created the opportunity for the UK to prosper, Covid has undermined the likelihood that we will.

We have ripped up a lot of institutions and conventions which it took us a long time to figure out were worth having. And I’m not sure we’ll enjoy the UK which develops without them.

What makes me claim all this?

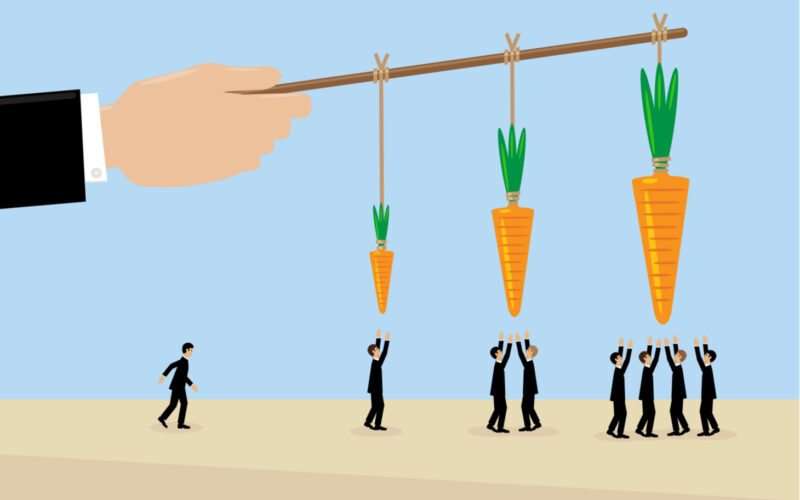

Warren Buffett’s partner in dime is Charlie Munger, who famously said, “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome”. The idea being that people behave according to their own best interests, so, if you can figure out what their interests are and how a decision impacts those interests, you can predict how they will decide.

Another Munger, by the name of Mike, is my favourite public choice economist. Public Choice Economics is based on the idea that “show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome” applies to politics as well. That politicians’ behaviour and decision-making is not driven by vision, ideal, ideology, patriotism, or any other high-minded concept, but by the incentives they face as individuals. The same goes for the civil servants running our government institutions.

This is blatantly obvious to some, but downright shocking to others. If politicians and civil servants are no different to us evil, selfish bastards who inhabit the distant world known as the “private sector”, what makes them better at running our lives than we could without them?

Just in case you were amongst the deluded, yes, politicians and civil servants are as self-interested as the rest of us. And so turning to them to run our society is a bad idea, unless you’re a politician or public servant yourself. In fact, giving such people power to lord over us is downright dangerous given the incentives they face.

Asking a politician or public servant whether we should lock down the economy during a pandemic, for example, will get you a reliable “yes” because, well, their incentives are obviously that way inclined. They pay no cost and gain a great deal of power in a lockdown.

If you buy into the core idea of Public Choice Theory Economics, let me ask you, how have the incentives changed post Brexit and Covid?

I’m sure you want the UK to be governed – however you want it to be governed. Especially post Brexit. But, let’s focus on what the incentives are, so that we can find out what’ll actually happen.

On trade, for example, we might want free trade with the rest of the world now that we’re out of the protectionist trade bloc of the EU. But the return of the lobbyists to the halls of Westminster means the incentives which politicians face are not that way inclined.

Who lobbies for free trade? Protectionism is a much more lucrative pitch – worth paying lobbyists and politicians for. And now, with the power to constrain free trade back in their hands, we’ll see UK politicians suddenly turn from advocating it to promoting protection for the industries they deem lucrative worthy.

Privatisation is the worst bungle of all, in my view. Just as the government mucks up running things, it also mucks up the process of privatisation. Civil servants, politicians and big business is the ultimate nightmare mix of misaligned incentives. The bizarre creations which result are from so-called “privatisation” are reliably disastrous.

Now that you’ve got a flavour for how this sort of thinking works, let’s turn to bigger matters.

The pandemic exposed that governments and central banks not only have vast power to lock down economies, they also have the power to prevent the consequences of doing so. Quantitative easing (QE) makes financing the government easy, evictions can simply be suspended, bankruptcies banned and cash handed out to anyone who needs it and to those who don’t.

I keep getting a cheque from the Japanese government, for no reason my wife can explain to me.

How does this new world change the incentives of politics?

Do you reckon paying attention to debt is going to be politically popular in a world that just “proved” it’s not something we should worry about?

Do you reckon austerity is going to be politically viable? What does that mean for the austerity advocates of the past?

Is there any worthy cause which shouldn’t be funded now that money is free and debt can just be bought up by the Bank of England?

If we can hand out cash to the needy during a pandemic, why not after and forevermore?

If central banks can print money to buy government debt, does that debt even count any more? And, as I heard on GB News itself, why can’t the government just repudiate the debt held by the Bank of England?

Politicians could even save the world from climate change with their newfound financial prowess.

You can see where this is going, can’t you? The incentives of politicians have fundamentally changed to promising things and spending big, because the restraints which stopped them in the past died with Covid-19.

The new post-pandemic normal might not include a pandemic, but how many pandemic policies will outlive Covid? How many Pandora’s boxes have been opened?

Historically, we got ourselves into a similar mess after a war, when national resources are commandeered and put to work in similar ways to the pandemic, while monetary policy sanity was left for dead. But, after the war, the bill that comes due is just too large to actually pay.

After World War I and World War II, the link to gold was gradually lost when governments met to decide what would be done to deal with the impossible debts and the monetary system.

When the Bretton Woods system which was implemented during WWII fell apart, suddenly, governments were no longer tied to gold in any way. They were free to spend as much as they wished, with only the consequences to stop them.

Unfortunately, democracies are not so good at making trade-offs between short-term gains and long-term consequences. They spent, borrowed and printed far too much money. And so inflation broke out. That’s all that reined in the unshackled politicians.

Well, it seems we just lost the key restraint on government spending again, just like we did in the early 1970s. That is because central banks have given away that they are willing to finance governments after all. And so, politicians need not worry about financing their mad schemes.

From here on in, the political incentive is to borrow, spend and print as much money as it takes to get elected. This has never worked out well in the past, but I’ve shown you the incentives, so you can see the outcome.

Nick Hubble

Editor, Fortune & Freedom