One thing I’ve learnt over the years is that you don’t mess with silver investors. They are a passionate bunch, and like to point out the times when I haven’t paid silver enough attention.

If I go too long without mentioning it’s “incredible upside”, I get the odd angry email telling me I’m failing them.

So that’s why we kicked off my Fortune & Freedom commodity take over special with silver.

But indulge me, as today I need to expand on this just a little more.

Because while those rapid silver fans, silver stackers or apes (I’ve lost track of all the sub silver groups forming now) will point to several reasons why the silver price should rise, they are missing the most critical one.

But first, a mining lesson.

Silver mining has declined in the past decade

There are lots of arguments as to why it should rise drastically.

One of the key reasons justifying a massive increase in the price of silver is that there’s not enough of the stuff coming out of the ground.

Which is somewhat true if you look at one area of silver supply – pure silver mines. In other words, those whose primary commodity is silver.

Over the past decade, less of the white metal is being mined from these. According to data from 2019, there’s been a 36% decline in ore grades from the world’s 12 largest silver miners. Meaning that there’s less and less silver in every tonne of earth dug up.

Not only that, but with the silver price slumbering for the past decade, silver mining companies carried out what’s called “high grading”. Basically, while the metal’s price was low, they were forced to mine the highest-grade ore to cover costs.

This means that, as miners dig away at their best stuff, it leaves the lesser-grade stuff in the ground –ideally to be extracted when prices are higher in the future.

When the silver price got a kick higher during the pandemic and once mine shutdowns ended, those higher prices did incentivise pure miners to move to some of the lower-grade product.

This compounds the problem, as it reduces the quantity of silver that finds its way to the market. Though, to be clear, supply of mined silver isn’t reduced so far as to cause a shortage. In fact, the market will be in a small surplus this year.

Yet, technically speaking, shouldn’t the shrinking supply of an already rare good increase its scarcity value and drive its price up? Well, yes. But silver is actually more complex than that.

The structural decline in silver supply

There is a structural decline in the supply of silver, but, at present, it’s a mostly a pure silver miner problem, where declining grades reduce the amount of silver mined each year.

This isn’t really a problem for miners where silver is mined as a by-product of another commodity.

While 26.7% of all silver mined comes from pure silver miners, almost three-quarters of newly mined silver comes from polymetallic deposits such as gold, lead, zinc and copper.

This distinction matters.

Supply of silver is dominated by metals other than silver. Meaning that more silver will only come to market as more base metals are mined and consumed.

Base metals are linked to economic activity. Economic growth means more base metals will be dug up to meet demand, in turn bringing more silver to the market.

This, by the way, is why the silver price has been kicked down to 2020 lows. Silver is mirroring copper’s reaction to slowing global growth, as well as China’s major city lockdowns.

Rather than pure silver miners, the world’s silver supply relies on base metals being found, extracted and needed by society.

The beauty of a polymetallic deposit that contains silver is that it acts as an offset on the cost of production of the other metals such as copper, lead or zinc.

The problem, however, is these other miners are usually not particularly interested in the silver. Even if the silver price rises, it’s highly unlikely to encourage them to go and find more.

To boot, pure silver miners have minimal elasticity: in plain English, they can’t dramatically increase supply in the event that the price soars. In fact, they would require a long and sustained silver bull market to invest the millions of dollars required to develop their reserves further.

We face a similar problem with scrap silver, which often fills the gap in the silver market.

At present, scrap silver makes up around 7% of total silver supply. While there is some sensitivity to the price, scrap silver is industry driven, not consumer driven. If the price rises, we are unlikely to rush off and cash in our electronic devices or knives and forks for a few bucks.

What all of this mining gobbledegook means is that the old economic adage “the cure for high prices is high prices” doesn’t really work when it comes to silver.

Anyway, now we have the information on how silver comes to us out of the way, we can get on to why the metal is never really going to be money again.

It’s too useful

So we end today where we started yesterday.

While there may be a time when gold forms part of the world’s monetary system again, it’s very unlikely that silver ever will.

Wednesday’s history lesson in bimetallic ratios is just that, history.

There’s no reversion to the century long mean of 50. There’s no plummeting back to a gold-to-silver ratio of 15, like in Newton’s days.

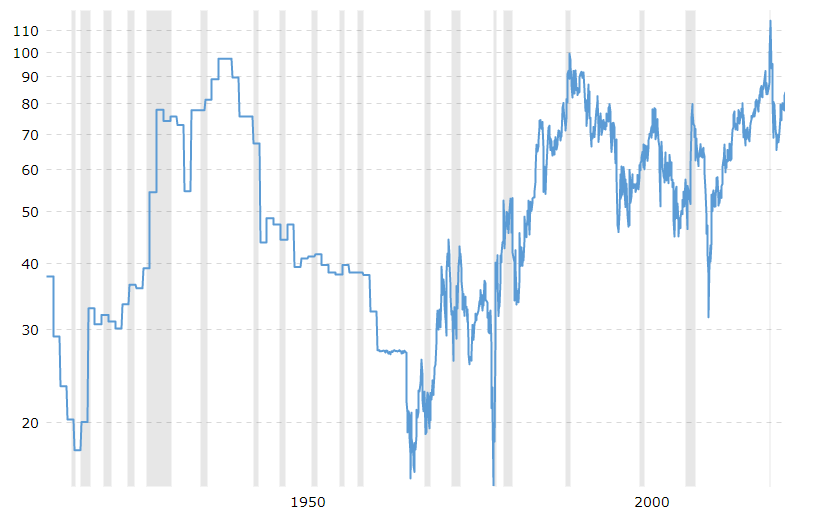

The gold-to-silver ratio average has been slowly nudging higher since both gold and silver became freely traded, and since then the increasing ratio (needing more ounces of silver to buy gold) is reflecting silver’s decoupling from money and its switch to an industrial metal.

Gold-to-silver ratio

1915 to present

Simply put, silver is too useful to society to just be money.

You can drink it, wear it or wrap yourself up in it. You use it to eat, absorb energy or send a message. No silver, no electronics. That’s no light switches, no computers, no phones, solar panels or wires. Because of its antibiotic properties, it is widely used in the medical industry.

Silver has superior thermal and electrical conductivity amongst the metals, and it can’t be easily replaced. It’s malleable and ductile, which means that it can be rolled, hammered or pressed into flat sheets, or drawn into a thin wire without splintering or fracturing.

In some industries, silver is used as a coating for copper cables for nanosecond (one-billionth of second) transfers. Adding a thin layer of silver speeds up the signal and reduces voltage drop.

It’s not the known uses of silver you should be watching, rather the unknown future use that could drive silver higher. Rapid changes in technology could put pressure on known supplies of the metal and, ideally, this is what nudges the price upwards for investors.

But any return to the good old days of silver being valued more closely to gold are gone.

In the past few millennia, silver has moved from being the only money that matters to being perhaps the only commodity we need more of in the future.

The industrialisation of silver is diminishing its role as money, effectively demonetising the metal.

It’s not that silver isn’t valuable. It’s just that its utility is now more important to us than historically.

Until next time,

Shae Russell

Contributor, Fortune & Freedom