“The stockmarket is just a casino.”

I must have heard or read this dozens, perhaps hundreds, of times in the nearly three decades since I first entered the weird world of finance back in 1993.

But is it true? Yes and no.

Yes, if you approach the stockmarket in the wrong way.

No, if you approach it in the right way.

How do I know? Because I usually have well over half of my own money, not including the value of my home, invested in stocks. Sometimes, when the opportunities are just too good to turn down, I have almost all of it there.

(Very occasionally, like just before the global financial crisis, I have virtually none. But that’s another story.)

As a long-term private investor, with an eye on eventual retirement or leaving meaningful assets to my kids, I believe the stockmarket is an essential place to be. But why?

Stocks, shares, equities… call them what you like. No one with an eye on preserving and growing their money should ignore them. Today I’ll show why I believe stockmarkets can be such a powerful source of profit for investors.

Shares are simply a way to have part ownership in the profits and assets of a business. If the business does well, and has responsible management, its investors (owners) will also do well over time.

That said, one thing is clear. Nobody should put money into the stockmarket if they’re likely to need it within five years, minimum. Preferably, they should plan to be invested for longer.

This is because stockmarket prices can swing around a lot. Sometimes that’s for good reasons, but just as often it isn’t.

Stockmarkets do crash from time to time, and prices can plummet indiscriminately in the panic. It’s just a fact of financial life. Markets are a crowd activity, and the market mob isn’t always rational.

No one should ever put themselves in the grim position of being a forced seller – namely, needing to sell something immediately at a bad price level. A crucial way to avoid that, when it comes to stocks, is only to invest money that you won’t need soon. (The other crucial way is to choose well.)

In fact, the longer an investor stays in the stockmarket, the higher the chance that they will make a healthy profit. By which I mean, returns that exceed consumer price inflation (and after any taxes due).

In other words, long-term stockmarket investments are a great way to grow the purchasing power of your wealth, right up to the point when you eventually need to spend it, such as in retirement.

Whereas leaving all your money in a bank deposit account, at current ultra-low interest rates, practically guarantees that you will lose purchasing power over time. That’s unless we get prolonged deflation, which seems unlikely in a manically money-printing world.

Here’s the nub of the matter…

Bank deposits are low risk in the short term, as they don’t go down in “price” (provided the bank is safe, of course). But they’re high risk in the long run, in the sense that your money loses purchasing power as inflation chips away at it.

Meanwhile, the stockmarket carries high short-term risk, as prices could drop suddenly just before you want access to your money (as happened in March this year). But it’s low risk in the long term, since stockmarkets have a well-established track record of returning more than inflation. Which means they can increase your purchasing power over time.

Cash for the short run, stocks for the long run.

Time is on your side

What’s my evidence for this assertion about stocks for the long run?

Well, there are masses of historical studies that show how stocks beat inflation over long periods. Plus, once you think about what an investment in a share represents, it becomes clear why this is so.

Let’s start with the history side. I’ll focus on one specific study which looks at how the odds of a strongly positive result get better over longer holding periods (but remain highly risky for short periods).

JP Morgan Asset Management looked at the range of returns between 1950 and 2018 for investments in US large caps (shares of big companies, such as those in the S&P 500 index, although that specific index was only created in 1957).

For various holding periods starting in any year within that range, they analysed the actual total returns that followed. The holding periods were 1, 5, 10 and 20 years.

Hence, for 1-year periods, the earliest year was 1950 and the latest was 2018. For the 20-year periods, the first was from the start of 1950 to the end of 1969 (start of 1970). The last was from the start of 1999 (end of 1998) to the end of 2018 (the last year of data in the study).

They then studied the range of average annual returns for each of those holding period buckets.

This is what they found (I’d love to put the chart here, but it’s protected by copyright):

- For 1-year periods: -43% to +61% a year

- For 5-year periods: -7% to +30% a year

- For 10-year periods: -3% to +21% a year

- For 20-year periods: +4% to +18% a year

The findings are clear:

- The longer the holding period, the less likely that investors suffered a loss and the smaller the maximum loss.

- Even the very worst 20-year holding period resulted in a positive result that averaged 4% a year.

- The longer the holding period, the smaller the range of average annual profits. Over one year, between the worst and best outcomes, the range of annual profit was 104 percentage points. Over 20-year periods, the range narrowed to just 14 percentage points.

Incidentally, the mid-points of those ranges point to average returns of about 9% a year. That’s about 6% a year more than the historical average US inflation rate of 3% a year.

This is consistent with other historical data for long-term US stockmarket returns that I’ve seen, such as that found in the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook (a reliable source of such data).

The data also shows that purchase price matters. Buying when markets are frothy, and prices are high, potentially leaves investors having to wait a very long time to make a profit. Getting good value always matters, even for the long-term investor.

The magic of “double compounding”

Why can stocks deliver these inflation-beating returns in the long run? What’s so special about them?

In my view, it’s down to stocks’ fundamental properties. It’s what I call their “double compounding power”.

Profit compounding is when investors make profits not just on their original investment, but also on past profits that they’ve reinvested.

Say I invest £100 at 10% a year. I make £10 profit in year one, giving me £110 at the end of the year. If I reinvest the £10, on top of the original £100, then I make £11 in year two (10% of £110). That gives me £121 pounds, which would make £12.10 in year three, taking me to £133.10 by the end of that year. And so on…

Each year, the profit increases (£10, £11, £12.10…). That’s because I’m reinvesting past profits on top of the original capital. This is profit compounding.

Of course, it doesn’t happen this smoothly in the stockmarket. Some years are better, others worse. But it still happens over time. And it’s very powerful.

If you invest in the stockmarket, your total profit comes from two sources.

First, you get capital gains, as share prices rise over time, although not smoothly. (Of course, this isn’t true about every single share, many shares go down in price too. I’m talking in general terms, and especially at the market index level.)

Underpinning these price rises is an increase in the underlying level of company profits and/or value of company net assets. (Which one is most important depends on the type of business.)

Some of this rise in value is caused by inflation, as companies raise their product prices over time to cover their rising costs (as the pound loses value). This means base profits also tend to rise with inflation over time.

Also, most companies keep a piece of their profits to invest in their own growth. In turn, this increases their value over time above the rate of inflation, which is already baked in. The result, if the investments are good ones, is that the value of the shares increases.

(Some companies may also use cash to repurchase a portion of their own shares in the market, something known as a buyback. The precise dynamics make for a complex subject, but the basic result is that the remaining shares become more valuable than without a buyback. This is because the company value is now divided between fewer remaining shares.)

The second source of stock investor profit comes from dividends. These are the portion of company profits paid out to investors as cash income. That income can be reinvested in more shares (of the same or other companies).

Combining those two factors – company growth and dividend income – explains the “double compounding power” of stocks for investors.

Investors in stockmarkets look to get:

- The growth in value of the stocks themselves, as companies reinvest a portion of their cash profits in the expansion of their businesses and profits also grow due to inflation

- Dividend income which they can use to buy more stocks.

Stocks for the long run… but not all of them

There is clear, historical evidence showing the likelihood that long-term investments in stockmarkets will comfortably beat inflation.

Also, the longer the investment period in stockmarkets, the lower the risk of making a loss. Provided investors have the willpower to stay the course during periodic market falls (which are actually great opportunities to pick up bargains with any spare cash and ride the recovery).

The reason stocks, on average, perform so well is due to their fundamental properties. That’s the double compounding power delivered by business growth and reinvested dividends.

That said, you do need to be selective and know what you’re buying.

The Japanese Nikkei 225 index is famously still around 40% below its early 1990 peak, when it was in a massive bubble. Thirty years later!

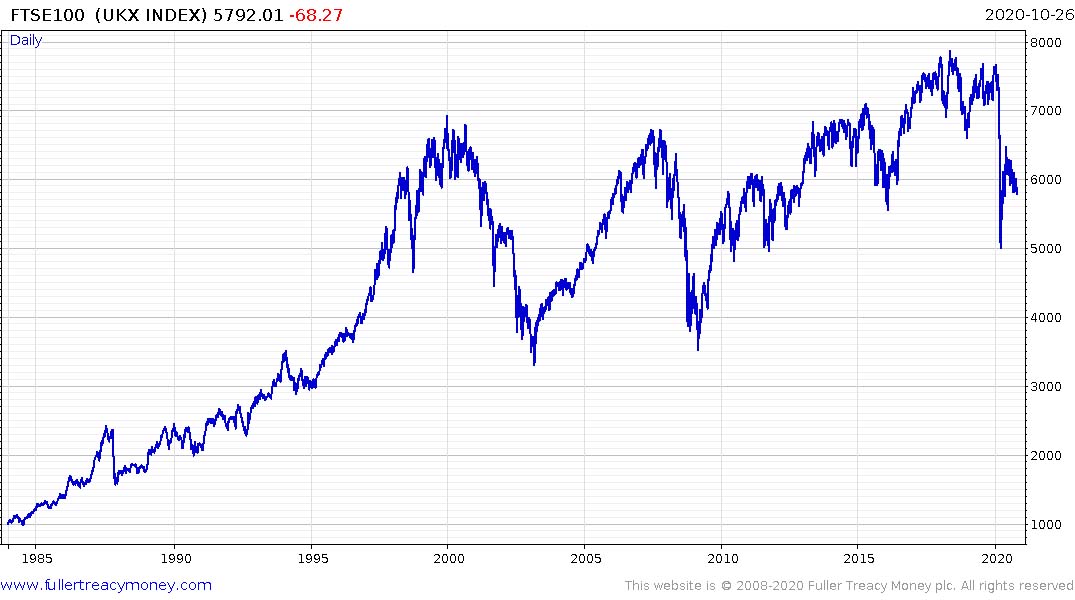

What’s more, the UK’s own FTSE 100 index of large companies has been a miserable place to be for a long time. It’s currently trading at the same level as it was in 1998, with some ups and downs along the way (as shown in the following chart which goes back to the early 1980s).

There are various reasons for that. UK bank sector shares have never recovered from the global financial crisis over a decade ago. And the FTSE contains a lot of shares of extractive industries (mining and drilling), whose fortunes are dictated by global commodity prices that have nothing to do with the UK.

But there are loads of great opportunities buried within the broader UK stockmarket. Current market prices are very attractive in many cases, which means they offer the prospect of strong investor profits in the future. Various things have caused this situation.

The painfully drawn-out Brexit process… worsening relations between the West and China… mainland Europe’s financial woes… the uncertainty in the run-up to the US election… and now the massive, global Covid-19 recession (partly self-inflicted).

All of these factors have weighed on prices in their own way.

But eventually the clouds will clear. There will be profits to be made.

Here at Fortune & Freedom we’re busily preparing to share our ideas with you, in the near future. Watch this space.

In the meantime, we’d love to hear from you (as always).

Do you think the stockmarket is a casino? Has your financial adviser left you invested in the dud FTSE 100 index for years? Have you tried a more direct approach yourself and selected your own stockmarket investments? How did it work out?

Let us know at [email protected].

Until next time,

Rob Marstrand

Investment Director, Fortune & Freedom