“A Black Sea mission to escort commercial ships may be needed to prevent a global food shortage,” The Wall Street Journal recently wrote.

“Am I reading this correctly”, you ask. “Warships to protect a grain shipment in peacetime?”

Yet that is exactly the situation policymakers are being forced into or the poorest in the world risk facing a food shortage. Roughly 50 countries rely on both the Ukraine and Russia for 30% of the world’s wheat imports.

Some 22 million tonnes of grain are estimated to be stuck in a Ukraine silo, and it looks like it could take a NATO-and-other-nations maritime effort to get them safely across the Black Sea and then through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles.

The grain blockade is coming at a time when 26 other nations have banned the export of certain goods. Lebanon has banned the export of ice cream and beer, which seems harmless enough. Indonesia has stopped palm oil from leaving its shores. Malaysia says that, as of June, it’s no longer exporting chickens.

None of these are sanctions-related either. These food bans are the local governments’ responses to food price inflation.

Food shortages are something that is associated with third world countries, yet the UK is at significant risk of facing a similar crisis. Why? Simply put, not much is home grown here…

Not much is grown here

Some people think about 50% of the UK’s food is imported, which is incorrect. It’s much closer to 80% of all UK food is imported.

The lower number just represents food made in the UK, but it doesn’t acknowledge that this food is made from imported ingredients.

International supply chains brought extraordinary choice in the type of food that is available here today. The problem is, it’s less a supply chain, and more like a complex web with insecure tethering points.

When one of those tethers gets blown about in the wind, the whole web flaps in the breeze.

Brexit happened, and goods and labour got caught up in paperwork snarls…

… then Covid…

… and now the Russian invasion is piling pressure on.

More to the point, it’s forcing those in the UK to face the uncomfortable reality of just how many things come from beyond its borders.

I’m not talking about all things Ikea, either. I mean food.

This makes Britons highly vulnerable to changes in both global food prices and supply disruptions.

And those disruptions may be about to get a lot worse.

Two months ago, the German headquarters of Aldi announced that up to 400 products will be “significantly more expensive” in the coming weeks. Many of us can look forward to price hikes of 20-50% on everyday items such as butter and meat.

Even this budget-friendly giant won’t be spared. And its situation isn’t unique. Not only are food prices increasing, but the prices of imports that make the food are also going up, which is putting extraordinary pressure on local farmers, and, in a worst-case scenario, risks food insecurity in the UK.

FarmingUK, a consortium that represents UK farmers, recently shared some alarming data.

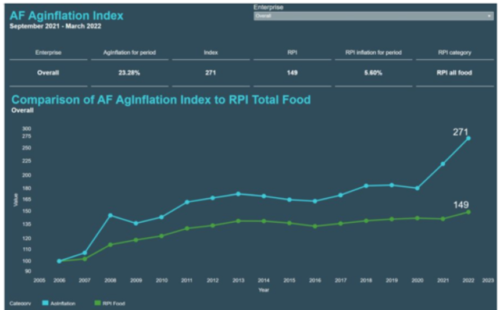

Its AF Aginflation Index showed a whopping 23% increase in farming inputs in the six months to March 2022. This comes on the back of a 22% increase in annual data reported in September 2021.

The consortium’s numbers show that four out of nine farming inputs saw double-digit increases in the past six months. The worst were animal feed (up 27%), fuel (up 29.4%), and fertiliser (up a whopping 107%).

Farming inputs compared to rising food costs Source: The AF Group Ltd

Source: The AF Group Ltd

To boot, there is a chance that these inputs have not yet made their way to consumers, judging by the sharp up curve in the AF Aginflation Index compared to the UK’s RPI Total Food inflation measure.

Thus we arrive at our two-pronged problem: not only have food prices got longer to run higher, but this is at a time when local UK farmers are likely to reduce their output.

You see, at present, farmers are the ones bearing the immediate cost of higher input prices such as fuel, animal feed and fertiliser. They are yet to be able to pass these costs on to manufacturers.

Because costs are rising so steeply, famers are actively reducing the number of egg-laying hens, or dairy cows, for example, because of the high cost of feed.

The immediate upside is more animals available for slaughter, with the result that few people see the pressure building. The consequence of this, however, is that breeding animals which replenish the flock or heard are gone. Breeding a new a flock is possible within a reasonable time frame. But rebuilding a heard of heifers and cows can take years.

Furthermore, even a useless urbanite like myself understands how critical nourished soil is for a successful harvest. Triple-digit price increases for fertiliser mean that farmers are faced with a no-win decision. Do they farm less land with what fertiliser they can afford to buy and produce fewer crops? Or do they farm more land with the normal amount of fertiliser in the hope they can yield the same crop quantities?

Smaller harvests, stock and farming animals hurt everyone in the long run. It starts with price increases and ends with a devasting reduction in food sources available.

More so, food insecurity risks lead to political instability…

You’re a consumer first and investor second

The question here is: what should an investor do?

Remember that you are a consumer first and an investor second. This is useful, because you can look at your own consumption behaviour to pick up on investment trends as prices rise and potential supply snarls become visible.

Second, invest like the big money does. Elon Musk may have recently shelved out billions of dollars for Twitter, but Bill Gates has been buying farms. Gates is now the largest farm owner in the United States with some 268,000 acres – and area roughly the size of Hong Kong – in his name.

Gates claims it’s not directly his decision, rather something his investment group is interested in: sustainable farmland.

Very few of us can gobble up land the way a billionaire does. Farming REITs (real estate investment trusts) proved very popular with the onset of Covid. They’ve had an amazing run in the last two years, though.

Other ideas may come from the support sectors to the farm industry. Keep an eye out for companies that are looking to reduce energy needed, fertilisers that don’t rely on gas and oil… and perhaps even innovative farming techniques that change how food is grown.

Until next time,

Shae Russell

Contributing Editor, Fortune & Freedom